Everything posted by Mark Jones

-

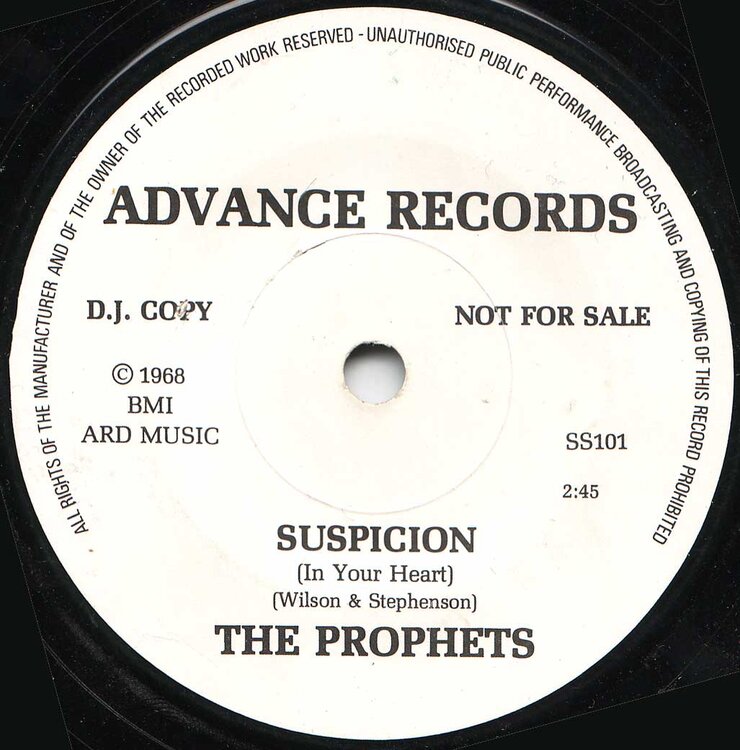

Prophets - Suspicion Bootleg

Found it myself! originals - suspicion - So where can I find this version? (what bootleg I assume?) never thought i'd be asking for a bootleg lol The version we usually here is this originals - suspicion -

-

Prophets - Suspicion Bootleg

Yep these were the first speeded up bootlegs as I remember, bought my scanned copy at Leicester Oddfellows allnighter when it was still a big play in the 80's for Rev Tony Clayton etc Here's the scan of my mine! OK the speeded up version we all hear (as per my scan)...which version is it speeded up from?... as the "normal" Original's version we all hear ain't this one speeded up. I'm sure I saw a post saying there are 4 or 5 versions of Suspicion....can someone post up the normal speed version of the speeded up version please? Bloody hell that was a tongue twister when you've had a few Friday night beers!

-

Chris Anderton On-Line Cat Radio Today 17.00- 19.00

You are welcome Chris...enjoyed it mate especially the last half hour that I managed to listen to eventually! Mark

-

Darrow Fletcher

I think you are right, did a search myself and nothing found. Maybe make one yourself, but might seem a bit mean if a birthday present! Got a few of his Northern cuts on vinyl (and mp3) "infatuation" and "what have I got now" being my fav's but not really enough to fill a CD.

-

The Jades On Poncello

Just as an aside are there a few Jades? I gather this ain't the same band that did Lucky fellow, where it's at, hotter than fire etc etc If so how many bands were called the Jades?

-

Chris Anderton On-Line Cat Radio Today 17.00- 19.00

looks like I'll have to listen the last half hour again mms://media.thisisthecat.com/TheCatOnDemand/Wednesday/17.wsx mms://media.thisisthecat.com/TheCatOnDemand/Wednesday/18.wsx Just copy and paste into your browser. Even listen again seems to buffer using winamp but OK using mediaplayer!

-

Chris Anderton On-Line Cat Radio Today 17.00- 19.00

Keeps buffering last 20 mins...like listening to Norman Collier anyone else got same problem?

-

Dream Team And Royal Esquires

Aplogies for the late replies guys. I'm sorted with both now thanks. Mark

-

Dream Team And Royal Esquires

Dream Team - There He is (Gregory) Royal Esquires - Ain't Gonna Run (HSI) soul source prices please! Imagine if I'd have posted this 10 years ago!

-

The Sound Of Keele

Same for me in 82....never knew them at the time...so exciting back then when all sounds were new at Leicester Oddfellows to my ears! Funnily enough I've just booked Nov 2011 off work so I can attend the Australian Nationals in Melbourne (where I happen to have relatives too) I went to last nationals in Melbourne in 2006 and it was so great to see a young crowd hearing the music for the first time! Oz is like UK 30 years ago...bloody love it!

-

Charles Mann - Hey Little Girl

Topping up my Stafford TOTW collection. Sensible prices please!

-

Miss Louistine

beautiful record for sure...late friend Steve Plimmer introduced me to in in the 80's,,,,class pure class

-

Could You Play?

hee hee...remember Keb saying this at TOTW Dave ...part of Keb's enivitable charm.....and we did dance....wouldn't argue with Keb!

-

How Many Records Arrive At Your House Per Week?

I've been accused of having an addiction...."why are you buying records that you just put in a box?" They may have a point but I explain it's a passion as well as a hobby...but they still go away expecting me to download the mp3 off itunes instead. Anyway I digress...I reckon I'm quite conservative (deffo not politically!) and only have about one to one point five records arriving "to put in the box" per week. Some top drawer expensive (600 quid my limit)... others not at all.....yes I do spend too much of my income on vinyl when I should be sorting my house out but what the hell I'm a bloke with a 28 year old soul passion! So are you spending too much of your income on vinyl (or styrene for that matter) too? Surely the new 3 piece suite can wait can't it?....so am I addicted? P.S....can you tell I'm single lol

-

Veep

What do we know about Elbie? I don't even know if he's black or white!

-

Veep

Please keep away just has to be my fav Veep track of all time...in fact it may be my fav track of all time but always hard to quantify that as so many favs Not only that it's my avatar too! Elbie Parker - Please Keep Away From Me -

-

Lee Fields Tsu Toronadoes Live Cover

Most of you already probably seen this but I hadn't....nice live cover!....pretty true to the original. Thought I'd share!

-

Edwin Starr...did We Take Him For Granted?

Wow!

-

Edwin Starr...did We Take Him For Granted?

like most we forgot that Edwin and Blinky were supposed to be the new Marvin and Tammi...just talent pure talent omfg this is good! another record to show off their partnership. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u-Q_W1jszGo

-

Edwin Starr...did We Take Him For Granted?

showing the talents we always were aware of but like me never heard. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fKd-cTyEsRQ&p=E08FEBCC2AA60423&playnext=1&index=28]

-

Edwin Starr...did We Take Him For Granted?

My god....Edwin..so good...

-

Edwin Starr...did We Take Him For Granted?

I need to go and pay my respects. Miss you Edwin https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IhB0msCGZiY

-

Edwin Starr...did We Take Him For Granted?

Can't imagine anyone having anything bad to say about the guy...one of my favourite songs by Edwin edwin starr - if my heart could tell the story -

-

Edwin Starr...did We Take Him For Granted?

Yes John agree with you...and thanks for your honest reply...think we all took him for granted as he was in our midst...miss his talent and still have a 100 questions to ask the guy!

-

Edwin Starr...did We Take Him For Granted?

Just a question really rather than a profound point of view...just now he's gone thought I'd ask the question of us all really....saw him many times and probablly because he lived in Stoke rather than Detroit anymore I always had the opinion... oh bugger I missed him this time but will catch him next time!....and now feel what a mistake that opinion was . I remember chatting to Charles Hatcher (aka Edwin Starr for those who don't know) about his life and his cousin Roger for that matter...such a lovely genuine man...he made everyone who met him feel special and never took his northern "fame" for granted. It was just as important to him that you liked his music and performance as much as he was pleased with it...he never forgot his fans...yes I know I'm stating the obvious for those who knew Edwin a lot better than me. It's not until i search youtube and realise that there's no recording of him singing "If my heart could tell the story" "I have faith in you" etc etc that maybe we all missed out on a golden oppurtunity even though we all probably saw him many times. Miss you Edwin Jonzy