-

Posts

2,086 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

3 -

Feedback

100%

Content Type

Forums

Event Guide

News & Articles

Source Guidelines and Help

Gallery

Videos Directory

Source Store

Everything posted by Rob Moss

-

Two versions by Fantastic Four. The single has strings. The album version doesn't and is a different vocal take.

-

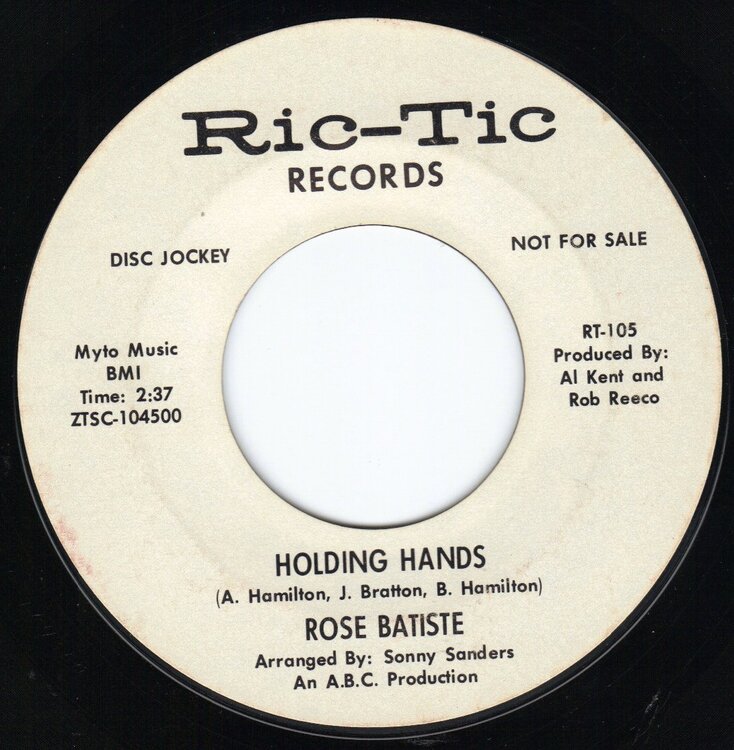

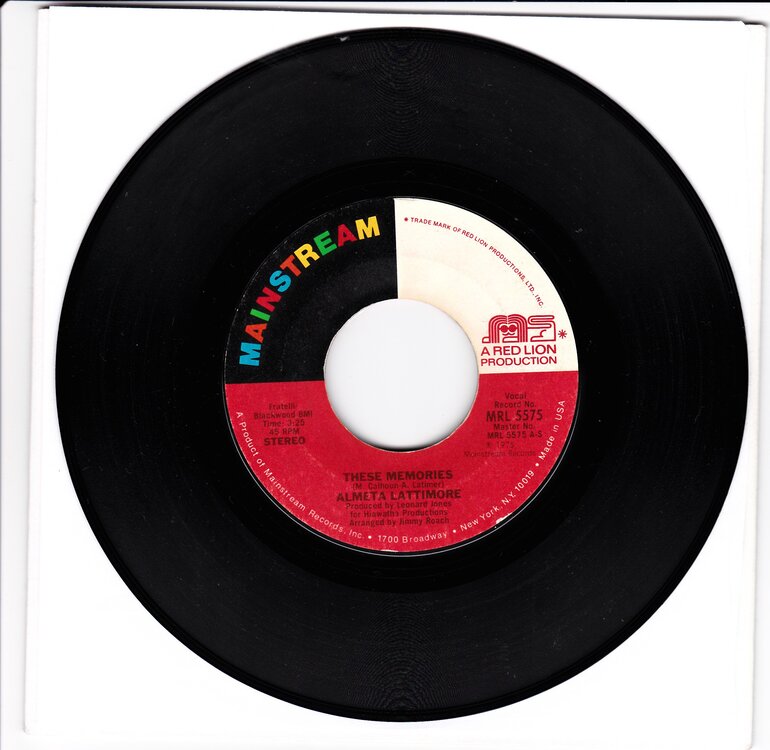

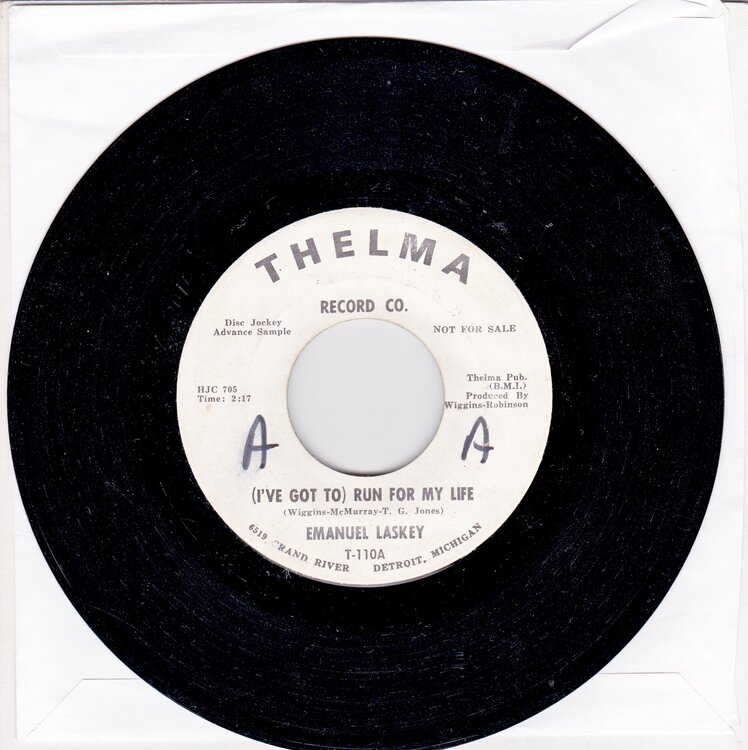

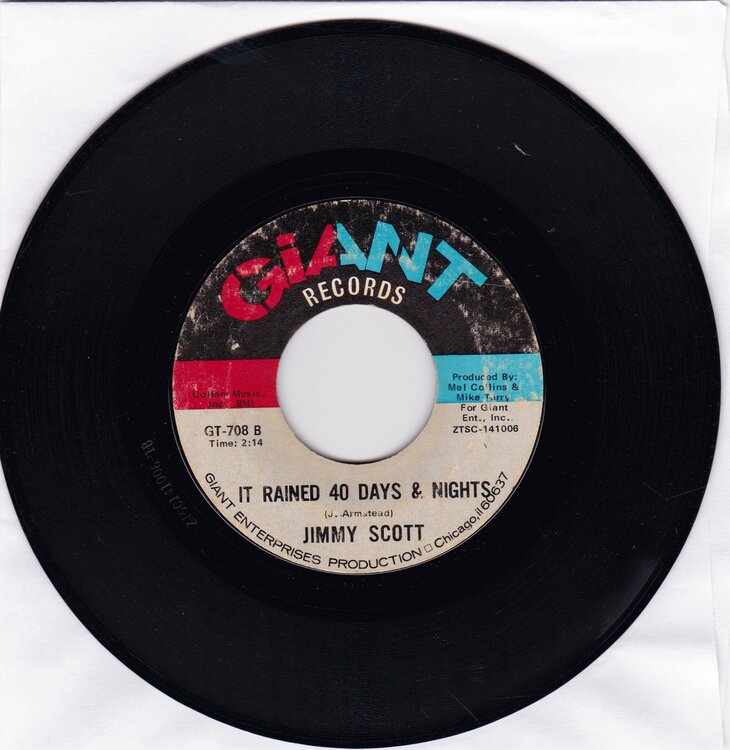

Following are for sale in £. PayPal OK (gift) Postage Royal Mail Special Delivery (£7.50 Insured) Overseas contact for details. Scans and sound files are from actual records. ROSE BATISTE Holding hands RIC TIC White Demo 850 rose b.mp3 ALMETA LATTIMORE These memories b/w Oh my love MAINSTREAM ISSUE 550 memories.mp3 EMANUEL LASKEY (Ive got to) run for my life THELMA WHITE DEMO 650 running.mp3 JIMMY SCOTT It rained 40 days & nights b/w Nobody but you GIANT 450 40 days.mp3

-

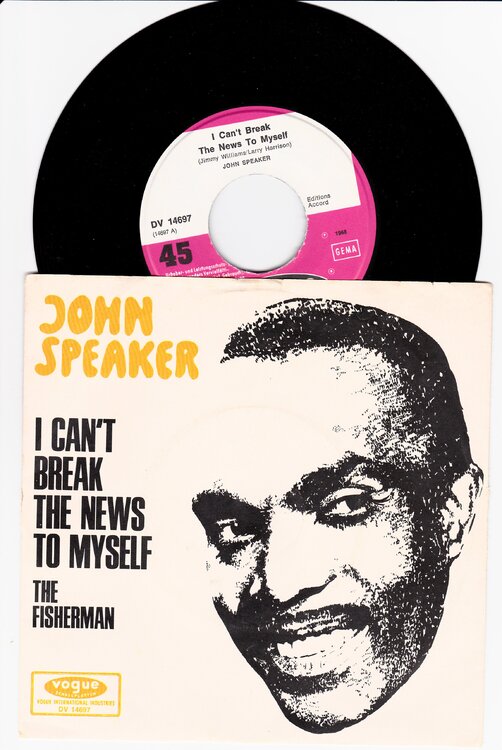

Brilliant version of Ben E. King classic. JOHN SPEAKER I can't break the news to myself German VOGUE in Ex condition. £80 PayPal (Gift) OK. Post £2 (Uk only) Contact for overseas rates.

-

The following are for sale. PayPal OK (Gift) Sound files available on request. Post £2 (UK) Contact for overseas rates. BOBBY FREEMAN I'll never fall in love again AUTUMN Promo VG+ Plays well. 40 JACKY BEAVERS Hold on SOUND STAGE 7 VG++ 50 RUBY ANDREWS I've got a bone to pick with you ABC Ex- 20 WALTER JACKSON Where have all the flowers gone/I'll keep on trying OKEH VG Plays well 15 MARY LOVE/DANNY MONDAY EP Lay this burden down/Baby without you UK KENT Promo Ex- 15 STRINGS 'N THINGS Fabulous New York/Charge JET SET VG++ 20 HIGH INERGY Make me yours (Brill. take on Betty Swann classic) GORDY White Promo Ex 12 INTERTAINS Gotta find a girl UPTOWN VG Plays well 20 RENA SCOTT Finally found the love EPIC Promo Ex 10 JACKIE WILSON Who who song BRUNSWICK VG+ 12 FALCONS I can't help it BIG WHEEL VG Plays well 12 SHARPEES Tired of being lonely ONE-DERFUL VG+ 15 DRAMATICS Inky winky wang dang doo WINGATE VG+ 10 SOLD PERCY SLEDGE Baby help me ATLANTIC M- 12

-

Edwin Starr - You're My Mellow - Recording Session Info Please

Rob Moss replied to Premium Stuff's topic in Look At Your Box

George McGregor is on hundreds of Detroit records including many Ric Tic, Golden World recordings, Thelma Records, Topper, Sidra (Musical director) et al. His style is distinctive by how 'busy' he is. His musical background was in a marching band. Brilliant producer and songwriter too. Was married to Barbara Mercer -

Edwin Starr - You're My Mellow - Recording Session Info Please

Rob Moss replied to Premium Stuff's topic in Look At Your Box

Drummer is def. George McGregor, baritone sax is Mike Terry (who else !), bass is Bob Babbitt, keys are probably Joe (Hunter) guitars are probably between Dennis Coffey, Don Davis, Eddie Willis and Robert White. Girls sound like Pat and Diane Lewis, but it could be Elsie, Joyce and Dorothy (Debonaires). There is a slightly different mix to the song that features Edwin ad libbing at the start and a more prominent part for the baritone in the mix. Recorded at either United Sound Studios or Theme Productions because Berry had taken over the Davison address by then. -

Following are for sale.All original US issue unless stated. PayPal OK (gift) or 4%. Post £2 for first record (UK only) Photo and sound file available on request. LEE ROGERS I'm a practical guy/ Go go girl D TOWN VG+ 12 DAVID RUFFIN Common man White Promo BS Ex 10 IMPRESSIONS You've been cheatin ABC PARAMOUNT VG (Plays well) 8 BUCKINGHAMS Don't you care COLUMBIA VG+ 8 LEN JEWELL All my good lovin/Betting on love SOUL CITY UK Ex 6 BETTY WRIGHT If you love me like you say you love me ALSTON VG+ 8 ZZ HILL Don't make promises KENT VG+ 15 DEON JACKSON Hard to get a thing called love CARLA White Promo VG+ 15 EDDIE HOLLAND Candy to me MOTOWN VG (Plays well) 8 JOE MATTHEWS Sorry ain't good enough THELMA VG+ 18 SOLD WONDERETTES I feel strange RUBY VG+ 18 SOLD AL WILSON Be concerned PLAYBOY VG+ 8 RAMSEY LEWIS Wade in the water (Blue) CADET VG+ 8 CHARLES MANN I can feel it ABC Ex 10 LOU RAWLS You can bring me all your heartaches CAPITOL VG+ 8 ODDS & ENDS Yesterday my love TODAY VG+ 8 INEZ & CHARLIE FOXX No stranger to love MUSICOR VG++ 8 JIMMY RUFFIN Since I lost you SOUL Ex.(No. on label) 12 LEE ROGERS Boss love D TOWN Ex 10

-

Bbc Tv 4,31St May At 9Pm, Otis Redding,soul Ambassador +++

Rob Moss replied to De-to's topic in All About the SOUL

Thoroughly enjoyed both programmes. Such a pity that it took the BBC so long to make the Otis one and show the 'live' show. Very annoying that they've been sitting on this stuff for such a long time. Wonder what else is available. -

There's an unreleased Perfections on E Bay at the moment.

-

Yes, I thought I saw him a couple of times ...and his sister. He actually appeared on Swingin' Time performing 'This won't change' I've seen a photo of it.

-

Swingin' Time was actually broadcast from Windsor, Ontario, Canada and not Detroit. Members of the regular dancers on the show were twins, Leslie and Lester Tipton.

-

John Speaker, Billy Thompson + Reasonable Offers Considered

Rob Moss replied to Rob Moss's topic in Record Sales

Reasonable offers considered for the following. Silly offers will be ignored. Post £2 (UK only) Contact for overseas rates. PayPal OK. Sound files available. JOHN SPEAKER I can't break the news to myself VOGUE (Germany) with picture sleeve. Ex/Ex 100 THE PERFECTIONS I just can't leave you WHITE LABEL (Unreleased) Only a few made.Same as Tony Hestor 75 WILLIE HUTCH I can't get enough MODERN White Promo (Slight label wear) Ex- 50 BILLY THOMPSON Black eyed girl WAND (Company sleeve) VG+ 125 RUDY ROBINSON & HUNGRY FIVE I smell a rat MIER (Detroit) VG+ 45 DARROW FLETCHER What good am I without you JACKLYN Ex- 100 WONDERETTES I feel strange RUBY ( 1st local issue) VG+ 45 JOE MATTHEWS Sorry ain't good enough THELMA VG+ 40 BEVERLEY & DUANE You belong to me BROWN BOMBER VG+ 125 FINAL DECISIONS You are my sunshine HI C VG+ 100 SHEILA FERGUSON How did that happen LANDA White promo Ex- 75 GLORIA TAYLOR You got to pay the price KING SOUL (Rarest label) VG+ 75 -

Following are for sale. Post £2 (UK only) Contact for overseas rates. PayPal OK. Sound files available. JOHN SPEAKER I can't break the news to myself VOGUE (Germany) with picture sleeve. Ex/Ex 100 THE PERFECTIONS I just can't leave you WHITE LABEL (Unreleased) Only a few made.Same as Tony Hestor 75 WILLIE HUTCH I can't get enough MODERN White Promo (Slight label wear) Ex- 50 BILLY THOMPSON Black eyed girl WAND (Company sleeve) VG+ 125 RUDY ROBINSON & HUNGRY FIVE I smell a rat MIER (Detroit) VG+ 45 DARROW FLETCHER What good am I without you JACKLYN Ex- 100 WONDERETTES I feel strange RUBY ( 1st local issue) VG+ 45 JOE MATTHEWS Sorry ain't good enough THELMA VG+ 40 BEVERLEY & DUANE You belong to me BROWN BOMBER VG+ 125 FINAL DECISIONS You are my sunshine HI C VG+ 100 SHEILA FERGUSON How did that happen LANDA White promo Ex- 75 GLORIA TAYLOR You got to pay the price KING SOUL (Rarest label) VG+ 75

-

The Best Of Unreleased Tamla Motown N.soul?

Rob Moss replied to Mick Sway's topic in Look At Your Box

The original was recorded by Ivy Jo Hunter -

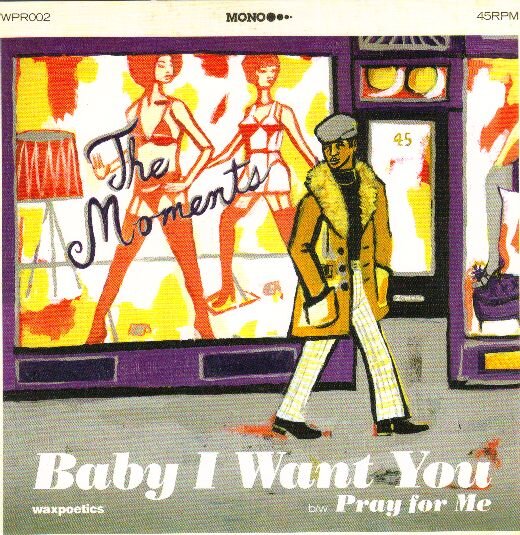

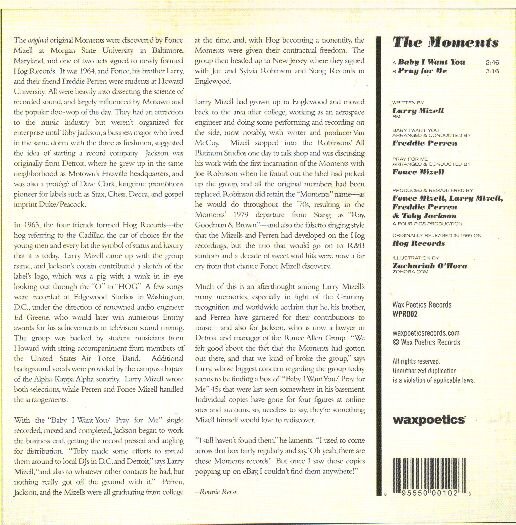

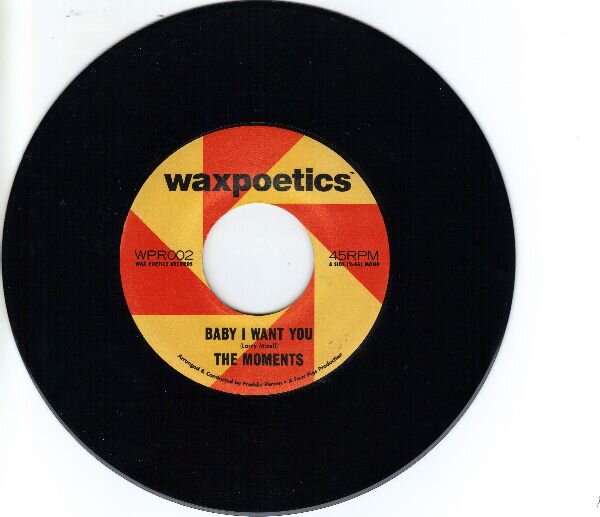

Got a couple of these for sale.Mint with picture cover. (See photos) £10.99 inc. post (UK only) PayPal OK (Gift)

-

Got a couple of these for sale.Mint with picture cover. (See photos) £12.99 inc. post (UK only) PayPal OK (Gift)

-

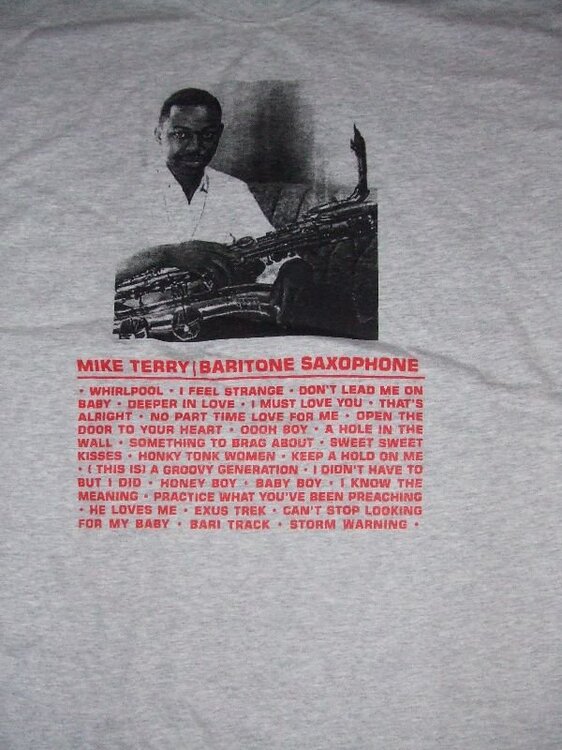

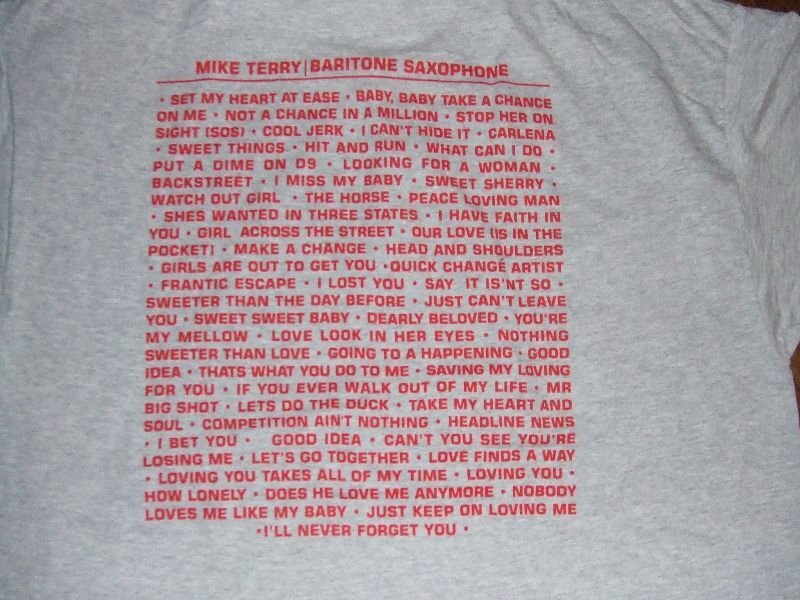

Two left only. Both XL. Tracks he played on both sides (see photo) £15 each (Inc. post UK only) PayPal (gift) OK. BACK FRONT.

-

Following are for sale. £8 each plus £2 post (UK only) or 6 for £40. All are VG/VG+ unless stated and play well. PayPal OK (gift) Sound file available on request. All US issue unless stated. FANTASTIC FOUR I'm gonna carry on SOUL SPENCER DAVIS GROUP Somebody help me ATCO White Promo ROSCO ROBINSON That's enough WAND FRANKIE VALLI You're ready now PHILIPS UK ALLEN TOUSSAINT Get out my life woman BELL Ex. SPINNERS Are you ready for love ATLANTIC FOUR TOPS Love is the answer MOTOWN Ex/M- COMMODORES Don't you be worried MOWEST White Demo BS Mint PERCY SLEDGE Baby help me ATLANTIC Ex BETTY WRIGHT Lovin is really my game ALSTON Ex FALCONS I can't help it BIG WHEEL BILLY PAUL Only the strong survive PHILLY INT. OLYMPICS Baby do the Philly Dog MIRWOOD GAYLE McCORMICK Gonna be alright now DUNHILL Ex HB BARNUM Baby, love me CAPITOL Green Demo LEE DORSEY Go Go girl AMY Ex TIMMY SHAW I'm a lonely guy WAND JOEY KINGFISH Just one more time D.WRECKED. HIT Mint RUBY ANDREWS Away from the crowd ZODIAC RUBY ANDREWS Casonova ZODIAC LITTLE MILTON Bet you I win STAX Ex JERRY O Karate boogaloo SHOUT FREDA PAYNE Bring back the joy CAPITOL THREE DEGREES There's so much love all around me ROULETTE Ex TRAMMPS I feel like I've been livin' ATLANTIC Promo Ex BS Al GREEN Let me help you BELL Ex. MARGIE JOSEPH & BLUE MAGIC You and me got a good thing going ATCO WILSON WILLIAMS All that glitters is not gold ABC LORENZO'S SOUL TREATMENT Keep an eye MINIT Ex HONEY CONE The day I found myself HOT WAX Ex OTIS REDDING Try a little tenderness (Live at Monteray) ATCO White DEmo RUBUY ANDREWS You made a believer out of me ZODIAC

-

Brilliant record. There is a vid on YouTube with a superb photo of her.

-

Following are for sale at £7 each plus £2 post (UK only) or 6 for £40 plus post. All are VG to VG+, unless stated, and play well. Sound files available on request. PayPal (gift) OK. All US issue unless stated. FREDDIE SCOTT Where does love go COLPIX MIKE JEMISON Quick change artist GENEVA Ex.SOLD NORTH BY NORTHEAST Pain of city living PROBE CHARLES MANN I can feel it ABC Ex LONNIE B & VIKI G Lovin' feeling REVUE LOU RAWLS You can bring me all your heartaches CAPITOL SUGAR BILLY Super duper love FAST TRACK White Demo SOLD PAUL MAURIAT Black is black PHILIPS White Demo SANDY WYNNS Love belongs to everyone CHAMPION SOLD ODDS & ENDS Yesterday my love TODAY INEZ & CHARLIE FOXX No stranger to love MUSICOR Ex IMPACT Give a broken heart a break ATCO BS Demo Ex LEN JEWELL All my good lovin SOUL CITY UK Ex RAMSEY LEWIS Wade in the water CADET DRIFTERS Baby what I mean ATLANTIC THE TREASURES You ain't playin' with no toy MERCURY Demo Ex AL WILSON Be concerned PLAYBOY Ex THE BABY DOLLS There you are GAMBLE INDEPENDENTS Arise and shine WAND Ex JOHNNY MATHIS Life is a song worth singing COLUMBIA FOUR TOPS Don't let him take your love from me MOTOWN RHONDA CLARK Sugar SPECTRUM X Ex THE MAD LADS Tear maker VOLT DELFONICS Loving him PHILLY GROOVE SYL JOHNSON I wanna take you home to meet momma HI THE JAMES BOYS The horse PHIL L A of SOUL BETTY WRIGHT If you love me like you say you love me ALSTON EDDIE HOLLAND Candy to me MOTOWN SPINNERS I'll always love you MOTOWN DAVID RUFFIN Common man MOTOWN White Demo BS Ex IMPRESSIONS You been cheatin ABC PARAMOUNT BUCKINGHAMS Don't you care COLUMBIA ALBUMS All albums are £13 each plus £3 post (UK only) in Ex/Ex con. PayPal OK (Gift) CLARA WARD Hang your tears out to dry VERVE (Inc. The right direction) VAN McCOY Soul improvisations BUDDAH (Inc. I would love to love you) DETROIT GOLD Vol 2 SOLID SMOKE (Inc. 'Ain't gonna give you up' VOLUMES, 'You better move GAMBRELLS) DEON JACKSON His greatest recordings SOLID SMOKE (Inc. Unreleased 'The reason why', 'Still remember the feeling' plus more) MANDRILL New world ARISTA (Inc. 'Too late') CHRIS BARTLEY The sweetest thing this side of heaven VANDO (Inc Gotta tell somebody) JACKIE WILSON Whispers BRUNSWICK (Inc. My heart is calling)

-

Following are for sale at £8 each plus £2 post (UK only) or 6 for £40 plus post. All are VG to VG+, unless stated, and play well. Sound files available on request. PayPal (gift) OK. All US issue unless stated. FREDDIE SCOTT Where does love go COLPIX SWEET DELIGHTS Baby be mine ATCO SOLD MIKE JEMISON Quick change artist GENEVA Ex. NORTH BY NORTHEAST Pain of city living PROBE INEZ &CHARLIE FOXX I ain't going for that DYNAMO SOLD CHARLES MANN I can feel it ABC Ex LONNIE B & VIKI G Lovin' feeling REVUE LOU RAWLS You can bring me all your heartaches CAPITOL SUGAR BILLY Super duper love FAST TRACK White Demo PAUL MAURIAT Black is black PHILIPS White Demo SANDY WYNNS Love belongs to everyone CHAMPION ODDS & ENDS Yesterday my love TODAY INEZ & CHARLIE FOXX No stranger to love MUSICOR Ex IMPACT Give a broken heart a break ATCO BS Demo Ex BOBBY TAYLOR I can't quit your love TOMMY White Demo BS Ex SOLD LEN JEWELL All my good lovin SOUL CITY UK Ex RAMSEY LEWIS Wade in the water CADET DRIFTERS Baby what I mean ATLANTIC THE TREASURES You ain't playin' with no toy MERCURY Demo Ex AL WILSON Be concerned PLAYBOY Ex THE BABY DOLLS There you are GAMBLE INDEPENDENTS Arise and shine WAND Ex JOHNNY MATHIS Life is a song worth singing COLUMBIA FOUR TOPS Don't let him take your love from me MOTOWN RHONDA CLARK Sugar SPECTRUM X Ex THE MAD LADS Tear maker VOLT DELFONICS Loving him PHILLY GROOVE SYL JOHNSON I wanna take you home to meet momma HI THE JAMES BOYS The horse PHIL L A of SOUL BETTY WRIGHT If you love me like you say you love me ALSTON EDDIE HOLLAND Candy to me MOTOWN SPINNERS I'll always love you MOTOWN DAVID RUFFIN Common man MOTOWN White Demo BS Ex IMPRESSIONS You been cheatin ABC PARAMOUNT BUCKINGHAMS Don't you care COLUMBIA

-

All albums are £15 each plus £3 post (UK only) in Ex/Ex con. PayPal OK (Gift) CLARA WARD Hang your tears out to dry VERVE (Inc. The right direction) MARY WELLS Self titled 20TH CENTURY (Inc. He's good enough for me') SOLD VAN McCOY Soul improvisations BUDDAH (Inc. I would love to love you) DETROIT GOLD Vol 2 SOLID SMOKE (Inc. 'Ain't gonna give you up' VOLUMES, 'You better move GAMBRELLS) DEON JACKSON His greatest recordings SOLID SMOKE (Inc. Unreleased 'The reason why', 'Still remember the feeling' plus more) ROYALETTES The elegant sound of MGM (Inc.'Can't stop running away') SOLD MANDRILL New world ARISTA (Inc. 'Too late') CHRIS BARTLEY The sweetest thing this side of heaven VANDO (Inc Gotta tell somebody) JACKIE WILSON Whispers BRUNSWICK (Inc. My heart is calling)

-

Green onions!

-

The original piano used on all the Motown sessions is in Berry Gordy's mansion in Los Angeles. The one McCartney restored came from Golden World. Marvin Gaye recorded 'What's goin' on' at United Sound Systems NOT Golden World (Studio B).

-

The Singers That Could Have Been Big But Just Missed

Rob Moss replied to Sceneman's topic in All About the SOUL

Marvin Jones (Jack Montgomery) James Emanuel Laskey James Epps.