Recording Studio Techniques -How Things Have Evolved

Back in the 60's, recording studios were very different places

RECORDING STUDIO TECHNIQUES – HOW THINGS HAVE EVOLVED

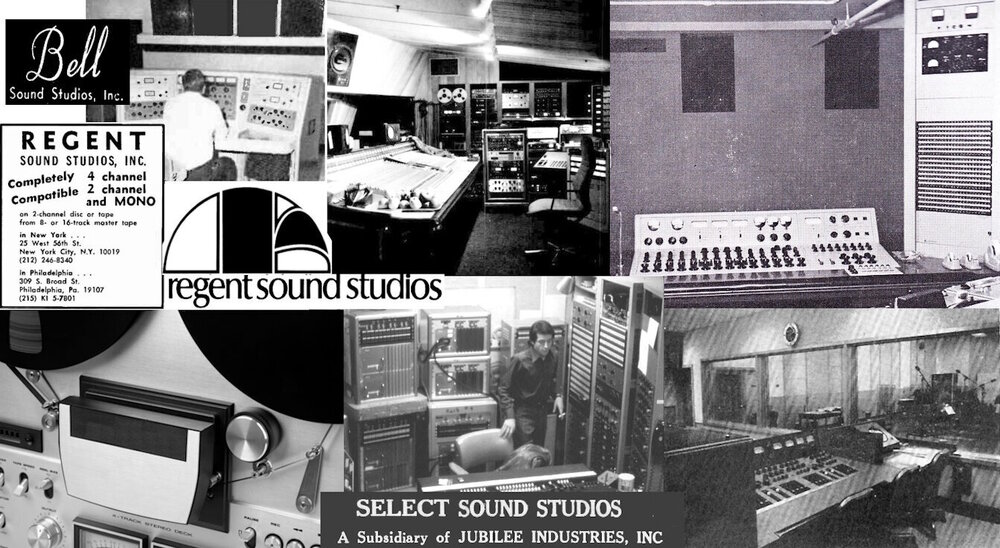

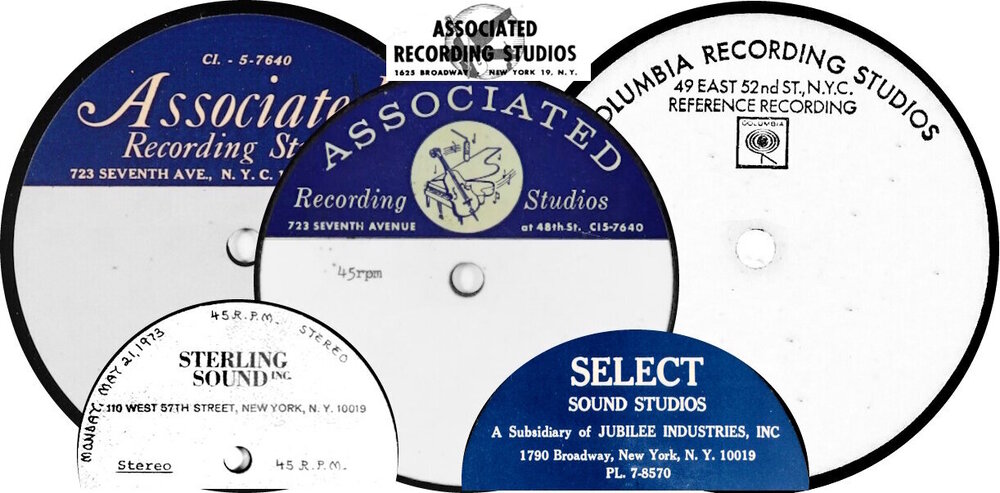

Back in the 60's, recording studios were very different places. The equipment wasn't that sophisticated at all. In fact, some recordings were just made on domestic tape recorders, with the group set up in a garage or similar space. Even professional studios would only have 2 or 4 track 'desk' equipment. As the decade progressed, the desks / studio rooms changed rapidly. But, even though the equipment was changing rapidly, the way many studios operated didn't. Of course, this wasn't true of every studio, but the studios run by the majors certainly stuck to old ways of operating much longer than was necessary. The majors (in the US & UK) also did things a tad more professionally than little indie studios (they had the money required). For example, to improve the acoustics of their studios, they would fix expensive sound deadening tiles to the walls. Indie studios would just collect loads of old egg boxes and nail those to their studio's walls to get a similar effect.

A few years ago, I was chatting with Johnny Pate about his days working for ABC Records in Chicago. He told me that his life was hectic back then because of the volume of artists ABC booked him to work with. His day ran from 9 to 5 with a lunch break. He'd turn up, look at the day's schedule & get straight into things. I asked him about some iconic tracks he was responsible for (Earl Jackson's “Soul Self Satisfaction” for instance) and he could not recollect even having done the session. He just worked with whoever was next on the list, laid down the required number of tracks with them and then it was straight onto the next act. He was committing so many tracks to tape, that many never even escaped from the tape vault. It was a crying shame, that in the 70's, the pencil pushers & finance folk @ ABC decided not to rent additional master tape storage space. Instead they issued instructions just to 'throw away' every tape that just contained unused tracks. Thus, almost every one of ABC's unissued Chicago soul tracks was junked in one go.

Traditional studios in the likes of New York and LA carried on, much like ABC, in their old ways of working. The day (usually) ran from 9 to 5. Producers, arrangers, musicians and the like were all booked ahead of time. Charts were drawn up for every track to be worked on and then the singer/s were brought in when everything else was ready. Before 1965, the track would usually be laid down with everyone in the studio at the same time. Very little 'change' was allowed to occur between the way the track was mapped out to sound and the final master tape version of that song. But sometimes things didn't run to plan. Frank Sinatra was booked for a session at a big studio but failed to show. Jerry Ragavoy was working away in the next room at the studio when an exec came in. He was laying down tracks cheaply on an unknown female soul singer. “We've got a full orchestra going spare, want to make use of them ?” Jerry happily jumped at the chance to 'upscale' his proposed session and thus we got Lorraine Ellison's “Sty With Me Baby” in it's full magnificence (+ the rest of her album).

Of course not every studio operated how the major's big city studios did. Over in Detroit, down in Memphis and Muscle Shoals things unfolded very differently. At the Hitsville studio and in Stax's building (an old movie theatre), the musicians were allowed free run. The session's producers would turn up with a few songs but nothing was set in stone. If the organ player or bass guitarist suggested a song would sound better if it was speeded up or if this riff was added into it, then that would be tried out. Thus, many sessions ended with tracks that sounded radically different to how everyone though they would sound at the start of the day. Booker T and the MG's were just 'messing about' when they came up with the riffs that went on to form “Green Inions”. This improvised way of working was allowed as the track was just going to form the throw away B side of a more thought out and structured tune they'd already laid down. But radio disc jockeys thought differently went presented with copies of the subsequent 45. They ignored the plug side, flipped the record & played the other side. Thus, the results of a last minute throw away jam became a massive selling track by complete mistake.

In the UK, recording studio methods of working were even more archaic. Musicians employed were in the musicians union. Producers had been brought up working on classical music sessions. So the producer, arranger & studio engineer were in total charge, except when the musicians said they weren't. Sessions commenced on time (9am) and ran through till lunch). An hours break was taken and work then continued till 5pm. At that point, everyone packed up and went home. That may have worked OK for disciplined classically trained musicians and singers but rock & rollers weren't like that. But, the studio only knew one way of working and so the 'new boys on the block' had to fall into line. However, it was the pop group guys (& girls) that were making the big profits for the major companies, not the classical recordings they also released. So things had to change, but that change came slowly.

The biggest change came about due to the pressure EMI's biggest selling act decided to exert. The Beatles had started out just like every other pop recording act. They had to do as they were told and work to the established system. But as their work continued to sell right around the world, the group's members realised that it was now them that held the winning hand. If they were half way through a track at 12 noon, they insisted the work to finish it continued. It helped, of course, that their producer was George Martin. He had worked on lots of sessions with comedians so was more used to 'adapting' to meet the day's circumstances. The group soon decided that there must be better ways of working in the studio setting. Things really came to a head on the Beatles 'Revolver' album sessions. The group were starting to experiment by then and broaden the 'sounds' they were recording. Thus, this group that had grown up loving and playing R&B were spreading their wings. The 'Revolver' album was released in August 1966 when the group were at the peak of their power.

Alongside old styled R&B tracks such as “Got To Get You Into My Life” they also wanted to lay down the likes of “Tomorrow Never Knows”. “Got To Get You Into My Life” was done quickly just as if they were playing live in some club or other, but “Tomorrow Never Knows” unfolded in a very different way. Sounds were committed to tape but then the tape was 'messed around with'. It was played more slowly than it had been recorded. It was played quicker, each set of sounds being captured on a new tape. The tape was then taken out of the player and stretched across the room. It was held in place by people holding up pencils and run around these. The master tape was then set in motion through the machine and the weird sounds created re-recorded onto a new track. There was no way that after having got everyone in place to do this tape spooling, a technician would be allowed to say “HEY, LET'S BREAK FOR LUNCH”. But that was a common practise before this session. The Beatles were like Gods at the time for EMI and so the technicians just had to buckle down and keep working till they were allowed to take their break.

In similar fashion, if one or more of the group was in full creative mode during a session, it didn't matter if the clock stuck 5, the session would continue until one of the group decided it was time to go home. Once the mold had been broken, there was no chance of putting the genie back in the bottle. Of course, this is how things had always operated in Motown's, Stax's and Fame's studios. It made sound commercial sense to keep going if a musical masterpiece was being worked on, whether it was 10am, 5.30pm or 11pm. At Motown, if someone like Berry, Smokey or Lamont Dozier had what he thought was a great idea for a song; the musicians would be given a call even if it was 2am. Of course, writers. producers, arrangers, musicians & singers also had lives outside of the studio, so not every call to arms was acted on. But with 24+ tracks now available on a master tape, as long as most of the required personnel turned up, the missing pieces could be added at a later time. Thus all the separate elements required for a fully finished recording would be captured onto tape.

By the mid 60's, technology had moved on. It was no longer considered adequate to have just 2 or 4 track machines on recording desks. Things had developed rapidly and it was now 24, 36 or 60 track machines that were being introduced in studios. Thus, sessions no longer had to unfold 'live.' The backing musicians could turn up separately and lay down a musical accompaniment for various tunes. Different backing singers could be utilised and their efforts committed to the tape too. Then the actual artist would be brought in (or a number of different artists in succession) and their lead vocals would be laid down. The studio engineer had become more important as he had to ensure all these separate parts were captured on the tape. The studio engineer had always kept recording levels at suitable volumes to ensure the sounds captured never sent the equipment involved up into the red zone. But this was no longer what everyone required. Pop, soul & rock acts utilised 'distortion' in their live shows and wanted this practise to also spread to their studio work. Thus groups such as the Who were pushing these boundaries during their studio sessions.

Other things were having to change too. Pop bands were used to heading out daily to undertake live shows. At these, they would set up their own equipment & instruments. A sound check would be performed ahead of the actual show & things sorted out to ensure the whole ensemble sounded good for their audiences. Thus the drummer, keyboard guy, guitar & bass player would all know how to mic up their instrument and which amplifier was best for the particular sound they desired. Over many months of setting-up in various different types of hall / venue, they'd learn what worked the best. But when they went into the studio, the technicians there insisted they knew better - where and how close each mic should be placed, etc. The sessions would unfold with the final track being committed to tape. The band would then listen back and soon discover that the sound they had wanted to achieve wasn't there. The likes of Eric Clapton soon got very shirty with the studio technicians. The technicians would insist the mic was set up 6 inches from his amp. He'd tell them that was completely wrong but they weren't used to having to listen. Of course, soon Eric had more sway than the technicians did, so the equipment was set up how Eric wanted it. That way, a Cream studio session would end up with recordings that sounded more like the band when they played live.

So, lots of vastly different sounds were being created in studio sessions in the 2nd half of the 60's. Because of this, alongside the singer / group themselves, the producer / sound mixer took on a much more important role. The likes of Phil Spector with his 'Wall of Sound' techniques had pushed recording boundaries a few years earlier. But now almost anything went. Studio tracks were now being manipulated / mixed such that it was becoming impossible to reproduce live the sound that had been captured on a track's final mix, the one that had gone on to get released. Soul music studios were a bit slower on the uptake. But then soul tracks relied more on the emotion captured on a recording rather than it's overall technical brilliance. Bum notes from one of the musicians were left in if they occurred on the take that had secured the best vocal performance. Of course, tracks were now being 'cut & spliced' even on soul sessions. Thus the first verse of take 3 would be chopped into the mid section of take 6 with the lead vocals from take 11 being superimposed over everything.

With this 'mix & match' system now becoming common place, the engineer at the sound desk and the producer took on more important roles. A 'finished track' might be worked on for many hours after the musicians / singers had all packed up and gone about the rest of their lives. In fact, by the mid 70's, there would be no such thing as the definitive & final version of a recorded song. The 're-mix' wizard would be called in and in no time there would be a 7” radio version, a 7” club version, a 12” monologue version, a 12” disco version, an 'instrumental only' version. Many tunes were being made available in 5 or 6 different styles – one being just 3 minutes 15 secs in length, while another version might run to a full 8 minutes. As 'mixing 'got more common, sections from an entirely separate old track might be added into the new recording. If the two tracks weren't set at the same BPM, then one (or both) would be manipulated till they did segue seamlessly.

As even more years passed, more & more different versions would be added into the recipe; X rated versions, radio safe versions, versions with an added rap section. Whole new songs would be constructed around a popular riff sampled from an old favourite tune. By the 80's, buying a 12” had become a complicated task. It was no longer safe to just go into the record shop and request a particular track by a certain artist. There would probably be six different 12” releases of the track and you needed to know exactly which remix you wanted to purchase – was the Dance Ritual Mix the one or the Quintero Beats version. So it's evident that the recording process had advanced enormously. What was accepted as a finished track in 1962, would no longer be acceptable. Each added section to a track's master tape back in 62 would have a higher audio level, meaning the first sounds laid down for a particular tune were now muddy and almost lost in the background of the entire concoction. Having more tracks on the master tape eliminated that problem, but introduced new problems.

Back to the early 60's; US major studios (especially in New York) started making big city soul sounds. The likes of Atlantic's producers Leiber & Stoller added strings and a Latin beat to some tracks. These recordings soon became hits and influenced what other studios went on to do. At Motown, Berry Gordy was creating the 'Sound of Young America'. Before long, every soul producer across the US was trying to reproduce that sound. People were sent to Detroit to suss out how that Motown sound was being achieved. Theories about the studio's layout being a major contributor became common place. Lou Ragland was sent over to Detroit by Way Out Records in Cleveland. He visited Hitsville and even got to work in United Sound Studios. He was just there helping out on local Detroit sessions it seemed. But in reality, he was spying for his employers and trying to discover the magic formula. Atlantic wanted their acts to have that 'raw sound' that Stax was achieving, so sent their acts down to Memphis. Stax saw what was happening and banned outside artists from using the studio. So Atlantic moved across to Muscle Shoals (where Chess were also sending their artists). Next up, the Miami sound became the in thing. So, lots of companies (including Atlantic) started sending their acts to cut @ Criteria in Miami. Philly had it's own thing going on, but in reality that sound only really took off in the early 70's.

R&B and then soul started taking off in a big way in the UK. So, beat group covers of US made black tracks became the in thing here. Some producers specialised in getting that sound down on tape in London studios. Before long, they were signing black acts who they knew could get closer to that original American sound than your run of the mill English group. John Schroeder was soon working with the likes of Geno Washington & Ebony Keyes. Peter Meaden also got in on the act; he was responsible for the best UK recorded soul album of all time – Jimmy James & the Vagabonds 'New Religion'. Other UK based black acts were also getting into British studios; the Chants (from Liverpool), Jimmy Cliff (before he switched to reggae), Jackie Edwards, Madeline Bell, Carl Douglas, the Foundations, Herbie Goins, Sonny Childe, Root & Jenny Jackson, etc.The releases of many of these artists failed to make the charts but that was because radio here failed to play list their tracks on a regular basis. The ship based pirate radio stations had done a great job of exposing the 45's put out by both US & UK soul acts. But the UK government soon shut them down and so there was less chance of new 45's by black acts getting decent exposure after summer 1967.

The 1970's brought much change to the world of soul music. The Viet Nam war had resulted in a reduction in love songs being recorded, with social commentary coming more to the fore. Soul was developing a harder sound and 'Jodie' was also beginning to appear as an important theme. The harder sound included the rise of funk and the introduction of psychedelic soul. Norman Whitfield spearheaded a change in the Motown sound but Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder soon got in on the act too. 'What's Going On' was a true musical masterpiece, while Stevie had gone off to play 'experimental instruments'. Stevie quickly became Motown's biggest selling artist, though his 70's sound was miles away from his earlier recordings. Soul music now played a crucial role in Civil Rights with artists using their platform to address social issues. Sly Stone had gone from DJing to fronting his band and the sounds he was making quickly became quite influential. Curtis Mayfield went solo and commenced on a new musical path that led to him becoming a movie soundtrack maestro. Down at Stax, Isaac Hayes also started pushing musical boundaries. Across Memphis, Al Green was cutting massive hits, but his sound stuck closer to more traditional soul music sound standards.

Apart from updating equipment to more modern standards, studio techniques on most soul sessions remained much the same. Keyboards such as the Fender Rhodes electric piano were replacing Hammond B3's on many studio sessions. Though recording techniques such as plate reverb and tape compression were employed in some studios. The more sophisticated desk equipment allowed production techniques to expand, with multi-layered vocal harmonies, sophisticated string arrangements, punchy horn sections, and complex percussion patterns becoming the norm. It was the likes of Motown & Philly International that pioneered the more polished tracks of that era. Guys who did push the boundaries included Jimi Hendrix (though he was much more loved by rock fans than by the soul crowd). George Clinton was also seeking a different sound to his 1960's output. At Chess, they had been watching the way UK blues rock groups were beginning to dominate the US & UK album charts. Not wanting to be left behind, they set up Rotary Connection, which Sidney Barnes played a major roll in. R&B and soul acts had, many times, grown up in the church singing gospel music. Lots of R&B songs were derived from an original gospel version. As time passed, the roles were reversed, with gospel acts re-wording hit soul songs to meet their requirements.

Since the 70's, the way studio's worked has continued to evolve. Even gospel acts now normally laid down their tracks in modern recording studios. We now live in a world where artificial intelligence is being used to make tracks. You no longer need real singers or musicians – a computer does everything. I've always dreamed of a world in which Otis Redding got to duet with Lorraine Ellison. This never actually happened, but I may soon be able to obtain a track on which an 'Otis & Lorraine' duet unfolds. Whether that will be a good thing or not, I have no idea. So, recording studios and their output has changed enormously in the last 60+ years. All the changes have resulted in us being getting better quality tracks, but it's highly debatable if the finished tracks are superior. For me, the simple & pure soul sounds that escaped from 1960's studios was music at it's very finest. If the technical qualities of many of those recordings left quite a bit to be desired, it seemed not to matter. Those cuts touched us on an emotional level on a far more regular basis than just about everything we get to hear these days.

Many UK soul fans crave a world where typical 1960's or 1970's track were still being laid down. Unfortunately, they find themselves having been shunted into a siding, the majority of those running recording studios these days not having that same desire. Some British soul fans have even gotten to spend time with the guys who originally ran studio sessions for 1960's / 70's soul sessions. They've discussed, with those present at the time, how particular tracks came about. What the personnel there did and what techniques were employed to arrive at the 'special sound' captured on a particular track. If wonder if they can enlighten us with anything relevant as to how things unfolded during those old 'special' studio sessions.

Recommended Comments

Get involved with Soul Source

Add your comments now

Join Soul Source

A free & easy soul music affair!

Join Soul Source now!Log in to Soul Source

Jump right back in!

Log in now!