Northern Soul - Melody Maker 1975

'The scene is here as long as the punters want it'

Another scan added to our reference feature. This one features a fairly lengthy look at the Northern Soul Scene from the Melody Maker music paper, the 25th January 1975 Issue, with the main focus on Blackpool Mecca and Wigan Casino.

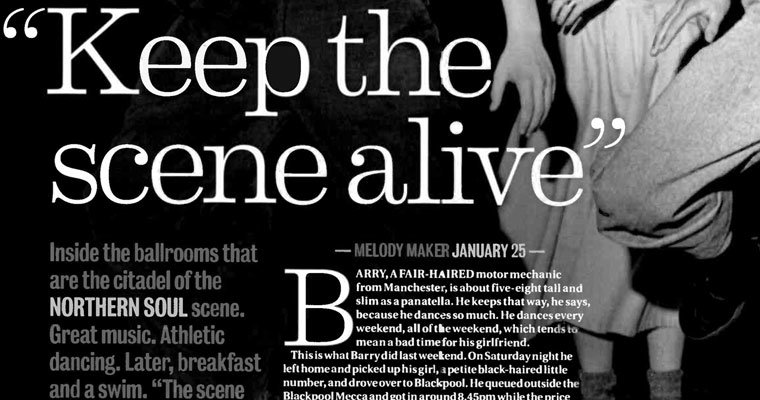

"Keep The Scene Alive"

Inside the ballrooms that are the citadel of the NORTHERN SOUL scene. Great music. Athletic dancing.Later, breakfast and a swim."The scene is here as long as the punters want it" says one DJ. "Its essence is rarity and it's up to us to keep that rarity".

Soul Source pdf embed article feature

A scan of a Melody Maker article dated January 25 1975, taking a look at the Northern Soul scene early 1975...

"Keep The Scene Alive"

Inside the ballrooms that are the citadel of the NORTHERN SOUL scene. Great music. Athletic dancing.Later, breakfast and a swim."The scene is here as long as the punters want it" says one DJ. "Its essence is rarity and it's up to us to keep that rarity".

BARRY A FAIR HAIRED motor mechanic from Manchester, is about five-eight tall and slim as a panatella. He keeps that way, he says, because he dances so much. He dances every weeknd, all of the weekend. On Saturday night he left home and picked up his girl, a petite black haired little number, and drove over to Blackpool. He queued outside the Blackpool Mecca and got in around 8.45pm while the price was still at its basic.The later you go the higher the admission price.

Barry was wearing a suit when he arrived. With a tie part of the Mecca's compulsory uniform imposed on patrons. He also carried a black Addias holdall. Barry and his girl went up a couple of flights of escalators past Tiffanys ballroom where a DJ played pop sounds and a clinically professional hose band played clinically professional versions of pop hits.By the time he reached the top floor Barry had his tie off.

Along a wide carpet corridor, groups of two, three, four guys talk, pouring over singles. Through the doors at the end of the corridor and into the Highland Room a long rectangular room, half of it lined with bars. The far wall is made of bare wooden panels except for a couple of doors; one long wall to the right is fronted by a low stage. On the stage behind a wooden hurdle is a disco, the focal point of the activity here.

Barry stayed there for about three and a half hours dancing a lot, chatting and drinking. Around midnight he left and drove to Wigan, it took about an hour. He and his girl had about an hour to kill when they got to Wigan. They spent it in a crowded, humid coffee bar full of guys like Barry, some with girls of their own but many without.

At 2am Sunday morning, Barry left the coffee bar and went into the Wigan casino. He changed out of his suit into a light blue vest and white baggies which were in the holdall and he put on a pair of less smart, though more comfortable shoes, and went into another dance hall. He danced there for something like six hours.

The Wigan Casino shut at 8am Sunday morning.Some of the kids went for breakfast and then took a swim to freshen up. Later they all drove to Burnley, where there was another disco, an all-dayer. There, they danced some more.

Barry does that most weekends. It's his scene, and he shares it with thousands of youngsters (their ages range from about 15 to 26, with most between 18 and 22). The scene is traditionally based on two things - the dance and the music, which is soul. It is not a new scene, its history stretches back some 10 years, but now the scene is changing through pressures of media attention and commercial exploitation. Several of those who've stayed with the scene throughout are worried by the recent glare of publicity, but most are confident that they'll weather the storm and re-emerge as unified as ever.

The reason for this thinking is sound enough, at least four of the DJs I spoke to at both the Blackpool Mecca and Wigan Casino expressed it with virtually the same words. "It's because," they'd say, their voices becoming serious and wise, frowning slightly, "that we're not the scene... it's THEM out there." And they'd point to the bobbing heads dancing concentrated to the sounds. I'd be inclined to agree with that.

A SHORT HISTORY OF the scene. It's been dubbed northern soul, but dancers and DJs alike seem not to care for the title. It goes back to around 1964-5 and The Golden Torch discotheque ballroom in Stoke-on-Trent. There, early Motown sounds were played, bands spawned by the soul boom gigged and a deeply knowledgeable sort of clan grew up.

Like any scene with a dedicated following, it also attracted the unscrupulous and the downright criminal, who would take any opportunity offered to rip the kids off. But the music remained intact. Other, more obscure records began to get played, their rarity value growing with the years. The sound, however, remained basically unchanged. A relentlessly fast snare drum snapping four to the bar; a booming bassline; sharp, toppy brass and/or strings, the vocals varying from intense expressive wailing to mechanical screeching, yet all compelling and involving. They drew you in and pulled you to the dance floor. The familiarity of listening to the same sounds every week, however, gradually bred contempt. The search for rarer sounds became more frantic -a record's lifetime on the decks became shorter. The turnover demanded was ever greater.

Inevitably the centre of the scene shifted, relocating itself to the North, in Manchester at the Twisted Wheel. There it continued to flourish for a while until it too dimmed and the axis moved on to Blackpool and Wigan. There, for the present, it remains. At the moment the Blackpool Mecca, reacting to the spiralling commercial interest in the scene and to the incursion of white music into a previously "black soul" area, is realigning its musical policy to include newer black music.

It is a difficult, costly business to maintain their policy of playing rare records as one of the DJs there, Colin Curtis, said: "I've only got to play a new sound two times and the next week there'll be a thousand copies pressed up or imported." Bootleg pressing are also something Blackpool, in particular, is campaigning against, with as great a tenacity as can be mustered. But the "purity" of the soul music played in Blackpool is, perhaps, the main concern and the difficulty experienced in such a pursuit is reflected i il a slight fall in attendances there (though this is something of a normal seasonal occurrence, according to the venue's manager).

Down in Wigan there are no problems filling the two halls, a large one functioning as the main scene, the smaller playing pop soul, rarity isn't so essential but danceability remains of essence.But there is one problem which the hall has to cope with. Despite the Casino's number one DJ Russ Winstanley assuring the Casino crowd that the all-nighters were in no danger, four guys, quite independently, came up to me and mentioned the likelihood of licensing trouble later this year, although Winstanley says that the Casino's operated for almost a year without a licence and has had no trouble from the authorities.

Whatever the future holds, whether it is forced to move on or not, it won't die. They, the dancers, the sweating, spinning, bouncing crush, will see to that.

BACK IN BLACKPOOL, Ian Levine and Colin Curtis do alternate hourly stints at the deck. Levine is a fat, blunt northerner. He offers a stiff hand to be shaken, its thumb sticking up like a flag pole. He looks away from you as you shake the proffered palm. His bluntness isn't rude. It's as businesslike as his introductions to the discs he spins.Ian has been Wing for some four years. He's been collecting records for eight years and has a fabled collection. He mentions how many and says he doesn't like that figure published. He used to work at The Twisted Wheel in 1971, went to The Golden Torch in 1972 for a spell and then moved up to the Blackpool Mecca where he's been ever since.

He gets his "rare, commercial" sounds from frequent trips to the States and is due to go over there in three weeks' time. He'll stay with one of The Exciters, who are great friends of his. He can finance these operations easily because his parents are wealthy and he has other records sent over by his relations there. All the time we're talking, leaning up against a wall in the corridor outside the Highland Rooms, people come up to Ian ("Don't call them kids... they're not," he says firmly).

They ask him about a record, about a future date, about something he promised to bring along. He seems an avuncular figure there, an impression strengthened by his initially distant manner. But, like Wigan, the scene in Blackpool attracts followers from all over Lancashire and, often, down into the Midlands. Coach parties from as far afield as Scarborough, Wolverhampton, Kidderminster, Harlow and Cambridge gravitate to the scene, drawn by the magnet of the sounds. Ian is introducing a greater variety of sounds into the records he's currently spinning. They used to be exclusively old records from the States which had barely caused a ripple in their homeland, let alone been released in Britain.

Nowadays he's playing records just released in the States (one of the last he played before we talked was taken from a new George Clinton album which may or may not be released here. By the time that happens it is likely that Levine will have stopped playing the track.) At Blackpool Mecca, Levine plays to a crowd of 800-900, which can go up to 1,300 or more. He only works there Saturday night but adds: "This is the one that matters to me. It's the scene that's made me England's top DJ" (He's very self-confident and assertive).

One noticeable comment from both Wigan and Blackpool DJs revolved around the music they played and their personal tastes. Few said the discs they spun were their own preferences. Ian listened to "something a bit more funky, but not basic. like Kool &The Gang." Ian is at once explicit and guarded about his relationship with the Wigan scene. He doesn't like the music much, because an increasing proportion is white British or white American, although it makes a suitable enough noise to dance to. But, as any of the DJs at Blackpool and Wigan are the first to say, it's the dancers who matter. Ian and Colin want to keep the music as pure as possible, Russ Winstanley, Richard Searling and the others in Wigan want to "please the kids; they're the ones, not our egos", as one put it.

COLIN CURTIS IS pipe cleaner lean. He has long straight hair which hangs over his shoulders. He's been at Wigan two years this March. He started out at the Stoke Mecca and then the Golden Torch all-nighters. He left there after "a disagreement". Now, including the Blackpool night, he works anything from four to seven nights weekly. Colin is as talkative as Ian Levine is reticent, yet he is no less blunt. A man for laying his cards on the table. He, more than any other I talked to, is concerned about the commercialisation of the scene by record companies, who are now plundering with the dynamism of Vikings. Few put in what they take out. This, I think is the crux. Currently, he's concerned "about the pressures on the punters. I don't want to make much of this so-called haggling between Wigan and the Mecca, especially if it gets the attention of the wrong types."

He feels "the punters are being immensely used. Just think, if soul music was in the same position as commercial pop music, think of the bread it'd be making." He doesn't see the past 12 months' interest in the scene as exploitative, but "it is the first nail in the coffin. This music has been underground and I hate to see it turn commercial, otherwise we'll be losing a lot of punters. "To keep the scene alive we have to keep in front of record wholesalers, because they can ring up the States once they hear what we're playing and get 1,000 copies imported. But the time lapse between us playing a sound and bulk copies appearing and killing it off is shrinking. How long can we keep that up?"

At the moment every record company in Britain is hip to the potential. Right from the time Robert Knight's "Love On A Mountain Top" went into the British charts late in 1973 after disco play had activated interest, the record business became aware of the possibilities inherent in such a fanatical and loyal bedrock of fans. Since then, Tamla Motown have re-released old favourites and Pye has launched Disco Demand, a label drawing its material from the scene and covering the whole spectra, almost scoring with The Casualeers' "Dance, Dance, Dance", finally breaking through with Nosmo King & The Javell's "Goodbye (Nothing To Say)" and Wayne Gibson's "Under The Thumb". Both the latter are white acts, both Wigan sounds, and both abhorrent to current Blackpool practice. Some record companies, he says, won't export quantities of singles under 6,000, and when a British importer can afford to buy in that sort of bulk and still make a profit... well, it doesn't take a whole lot of brains to wise up that here is a licence to print money.

"We're really scraping round to find records now. You can't fight it really, but we'll keep trying to... right to the end. "I mean, I could go to President and tell them what they've got in their catalogue that's worth releasing, but that's not what ! want to do. How many of the soul artists on Disco Demand have got into the charts? None, right? They're all white." And now, he reckons, there's probably going to be a TV documentary on the scene. That is another, somewhat larger nail in the coffin. "Why do they exploit the scene in this way? They're treading on people's ground, they've no feeling for it... We're going to lose a lot of good people if TV gets a grip... It'll be a sad loss for the soul scene in general if commercialism does take a hold. "But," he says, trying to end on an optimistic note, "the scene is here as long as the punters want it to be here... Its essence is rarity and it's up to us to keep that rarity."

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"The music's been underground; I hate to see it turn commercial"

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

AT 1.30AM SUNDAY morning, the queue outside the Wigan Casino, a large, red brick, grim looking edifice, is lengthening. Inside, the evening session is coming to an end. It's mainly pop. Through swing doors, up a couple of flights of stairs, through more swing doors, along a short narrow passage and through yet more doors. Out into a large hall. At the far end is the stage with curtains closed behind a deck holding three turntables and box upon box of records. The temperature in the place starts at hot, becomes humid,then stifling, tropical, equatorial. And the kids dance on A record starts to play. As it reaches a bridge the snare drum cracks out two beats. Every hand in the place, in perfect sync, appears to clap. There's a sound like a gun shot, a whip crack. That sound punctuates throughout the evening. These are the people who make the scene. There may be leeches who feed off their blood, pushers and bootleggers and other vermin, but the scene is firmly based on workaday punters who just want to dance, to be on the scene. The hall fills up. The dancers crowd closer together. The music is based on the same sound structure as the oldest Motown records that distinctive, fast slapping beat though the colour of the artist singing the beat is, at Wigan, increasingly immaterial.

Above the dance floor, around the wall of the hall, runs a balcony. Up there kids push through to the "pop" disco, a smaller hall though no less crowded, or shuffle through boxes of records, label less or otherwise, which are being hawked. The centre of activity switches between DJ and dancer. Faces turn to the stage as a record ends. A new one begins and the punters pickup the beat. Some jog into it slowly; others more sold on the particular sound being played this time fly with an effortless, often quite graceful, ease into a smooth series of kicks, pins, jumps and squats.

Gone are the suits and ties; now all is baggies with vest or bowling shirt.There are more blacks at Wigan than at Blackpool, though conversely less black music. There is the paraphernalia of Casino artefacts, posters sold to the kids, badges to sew on vest or shirt, car stickers. As the night wears on, 3am, 4am, the dance becomes more intent, exhausting. Kids go out fora Coke or sit slumped against a wall. One little fella, he has a light blue bowling shirt on is dancing 10 feet from the stage. A DJ puts a new record on. The kid stops dancing. He stands, expressionless but for a hint of petulance, with hands on hips. The record, you gather, is not to his liking. So there he stands while all around him bodies jiggle, twirl, hop and leap. You don't dance to something you don't dig. Behind the curtains, on stage, DJs congregate, chat to friends. Russ Winstanley is another podgy man and Boss DJ of Wigan. He isn't as worried about commercialisation as the Blackpool operators. He reckons the scene will be under close scrutiny "until about June or July. There'll be a couple more hits and then the fuss'll die down. Something like the reggae boom a few years back."

For Dave McAleer, Pye's A&R man up for the night, the testing time of the evening comes when he hands over a new Javells single to be played. As soon as the needle hits the groove there's loud, brash music louder than most of the records played. The kids, apart from a few small pockets of activity, stop dancing. It takes time to get a reaction and any unfamiliar sound is approached with a certain suspicious temerity. To dance or not to dance.

In the end, it's their decision which will decide how long the Javells record gets played; that goes for any new sound, no matter how rare, how black or how white. That, says Winstanley, is the way it should be. And then you notice them. The kids sitting and leaning along the stage. One girl is staring out at the dancers and, casually, her left hand holds a tape recorder microphone to the shuddering speakers. Then you notice another. And another. One more at the end of the stage. Finally, around 5am, it's time to leave the seething field of dance. Perhaps the most lasting memory of all was walking from one end of the Wigan dance floor to the other. It was like walking on a trampoline. The last I saw of Barry, the motor mechanic from Manchester way, he was jumping way above the other kids, a big, big smile across his sweaty face. Then he landed, did a spine breaking backward bend, came up and bobbed for a while. Then went into a spin, arms held tight across his chest like an ice-skater. He looked triumphant after that. The scene's his.

Geoff Brown

Edited by Mike

Related Soul Source Articles

-

9

9

-

3

3

Recommended Comments

Get involved with Soul Source

Add your comments now

Join Soul Source

A free & easy soul music affair!

Join Soul Source now!Log in to Soul Source

Jump right back in!

Log in now!