Don Juan Mancha - The Story by Rob Moss

a popular and well known figure on the music scene

Don Juan Mancha — songwriter, producer, musician and talent scout.

The name ‘Don Juan’ first appeared in the Spanish play ‘The Trickster of Seville and the Stone Guest’ by Tirso de Molina in 1630. The plot centres on a fictional libertine who devoted his life to seducing women. The term quickly passed into literary parlance as a synonym for a ‘womaniser.’ The story itself was rewritten numerous times throughout the centuries, in a variety of forms, including many plays, a poem by Byron, an opera by Mozart and a social satire by George Bernard Shaw, ‘Man and Superman.’ Don Juan Mancha’s legacy may not have the same longevity or notoriety as his famous namesake, but it remains a lasting testament to a long and distinguished career that spanned the second half of the twentieth century and beyond. His father’s Spanish roots provided all names for him and his brother Pedro. Mancha’s work with artists like Wilson Pickett, Edwin Starr, Betty Lavette, Ike and Tina Turner plus scores of others, for labels like Motown, Golden World, Thelma, Scepter and others, at numerous studios across America made him a popular and well known figure on the music scene, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s.

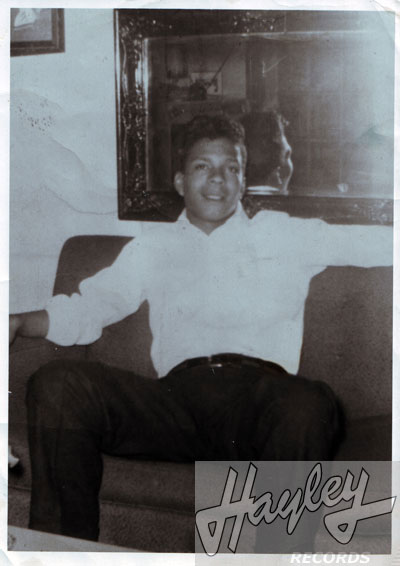

Don Juan Mancha

Although he is best known as a prolific songwriter, he also produced and arranged music, sang and played, and undertook various management roles. Unlike most of his contemporaries, he didn’t restrict himself to working in one city or region, but travelled extensively throughout the country to promote his songs, record, produce and arrange, building up an extensive network of contacts, colleagues and co workers along the way. Detroit was always home however, and it was in the Motor City that he produced his best work — with an array of local artists, either on his own or in collusion with some of the most talented songwriters and performers of the era. For ‘Rare soul’ enthusiasts his body of work contains some of the finest, and most sought after, material by the likes of Jack Montgomery, Martha Star, Just Brothers, Billy Kennedy, Billy Hambric, Honey Bees, Wilson Pickett and scores of others, many of whom he discovered.

Don Mancha’s teenage years largely comprised of schoolwork, singing and learning to play music, and a two-year stint in the U.S. Air Force. By the time he’d completed his military service, in 1960, the local music scene in Detroit, led by the early successes of Motown, was evolving into a vibrant and potentially lucrative environment. His first serious encounter with entertainment came in high school, as he clearly recalled “ We had a vocal group back then that we called ‘The Delrays’. Barrett Strong was our lead singer. I came up with a song called ‘Funny that’s what I want’ that we would do. I played piano and even auditioned for ‘Popcorn’ Wylie but that didn’t happen. I would do shows with the Delrays, but, to be real honest, I didn’t like singing and I didn’t really like the lifestyle. Even back then, I liked writing better, and working with artists and the musicians. I wrote a song called ‘Misery’ that I gave to Barrett and we took it over to Motown and recorded it on him. I guess that was the first song I ever did that I got paid for. Robert Bateman engineered that session and Sonny Sanders was there too with Popcorn and some of the others guys I would work with a lot in future days.”

If Mancha thought his career as a songwriter and producer would continue after the Air Force he was mistaken. “When I came out of the Service my buddy ‘Mack’ Rice called me to come and audition for his group, The Falcons. I guess Joe Stubbs had left and they were looking for a replacement. Mack had hooked up with Robert West at a company called Lupine, so I went over there. To start with they wanted me to sing. Robert cut a record on me, a thing called ‘Hong Kong’, which didn’t get released, but I just wanted to work with artists and write, so I signed a management contract and that’s when Mack found Wilson Pickett and we did ‘I found a love’. It was my song but I didn’t get a credit. I played piano on the session and Mack brought a guitarist in. They rest of the players were from Dayton, Ohio. They named them the Ohio Untouchables on the record. They went on to become the Ohio Players.” ‘I found a love’ became a huge national hit for the Falcons in 1962, and although Wilson Picket stayed with the group initially, he eventually joined a mini defection of personnel to join the fledgling Correctone set up over on Michigan Avenue. This included Bob Bateman, Sonny Sanders and ‘Popcorn’ Wylie who had all left Motown around the same period and Don Mancha.

He has happy recollections of his time at Correctone. “The label and studio was owned by Wilbur Golden. He was primarily a gangster I guess you’d say. He didn’t really care whether we had a hit. He put a lot of money into it because he used it as a ‘picnic’ — a place to show off to all his friends. He probably laundered dirty money too, but we didn’t care ‘cause he paid us well. We had Theresa Lindsey, Pickett, Gino Washington, the Pyramids, Danny Woods and the first artist I worked on there, Lillian Dorr. I did an answer song to ‘If you need me’ called ‘I need you’ Pickett was on a contract with the Falcons but he was always his own man and did what was in his own best interest. I was right in time with him when we joined Correctone. We did a single on him at there, ‘Let me be your boy’ that was later leased to Verve, who put it out again when he got hot in ’65, and we all worked on ‘If you need me’ with him. But Pickett worked in spite of himself and with ‘If you need me’ he blocked his own action. He went out on the road with the Falcons to New York where he did a deal with Lloyd Price to put the record out on his own Double L label, then sold the song to Solomon Burke who recorded it at Atlantic, so they both had it on the charts at the same time. Lloyd Price gave him a Cadillac to try and get him to break the management deal he had with Wilbur Golden, but he wouldn’t sign it so Lloyd Price took the Cadillac back!

I did a deal with Lloyd too around that time on a Detroit blues artist, Buddy Lamp that he put out on his label.” (My tears b/w Thank you love) Although ‘If you need me’ was only minor hit for Wilson Pickett, in the face of the better promoted Solomon Burke version, it did bring him to the attention of Jerry Wexler at Atlantic Records in New York, particularly when the follow up ‘It’s too late’ made some noise too. Mancha clearly remembered the sequence of events. “Things weren’t really happening for Pickett around that time and he became desperate. He was having to pay for his own sessions at Correctone, which led to him being pretty disillusioned with Mr. Golden and his staff. He didn’t feel any allegiance to them and started negotiating with Atlantic behind their backs. I went to New York with him in early 1964 when he finalised his deal. I’d written a song with him called ‘For better or worse’ and they used it as the B side to his remake of ‘I found a love’ that he cut for Atlantic.”

Back in Detroit, Mancha became involved in another fledgling music operation that would eventually provide competition for Motown’s domination. “Wilbur Golden had lost his shirt on Correctone. He’d lost his wife, lost contact with his family. Lucky for him, Wingate bought him out. He gave him some money and took the artists’ contracts, equipment, everything, but he wanted a bigger building so he bought the plot on Davison. It’s kinda funny that Wingate called it Golden World ‘cause the ‘Golden’ was actually Wilbur! Wingate was into the numbers racket and was well connected. He looked like Idi Amin and wore these baggy suits so no one knew what was in his pockets. The first thing I did for him was on Sue Perrin in New York, then we did ‘Deep freeze’ on the Adorables. That was Pat Lewis’ group. We did that at United Sound on three tracks — one vocal, two for music. Robert Bateman was a genius at placing mikes to get the best sound and he showed me how to do it and we reckoned it sounded just like a Motown record. Then I did Freddie Gorman sessions there too. ‘Take me back’ and ‘Can’t get you out of my mind’ were what we called ‘sneak’ sessions. They were recorded at 6 am ‘cause we had to wait for the musicians we wanted to come in when no one could see ‘em. We waited up all night to do that session.

Before Wingate purchased Golden World, all of the records we cut were done at United. His investment, and the faith he put in people like ‘Popcorn’ and Bob Hamilton, paid off big time too when the Relections hit with ‘Just like Romeo and Juliet’. That record helped launch the whole operation really.” Bob D’Orleans was commissioned by Ed Wingate to fit out the new studio with the latest ‘state of the art’ equipment, but the installation didn’t run as smoothly as hoped. “I remember the first day in there. Bob and his people had wired it wrong, or something, and when they turned the power on everything started shaking. The glass window in the control room that looked out over the studio started vibrating. I remember Al Hamilton was there with his brother Bob, and he shouted ‘She’s gonna blow!’ and moved outside real quick. Wingate came in and just grabbed the big tape wheels and ran off with them. That was so funny.” When normality was restored success quickly followed. “ I was writing with Bob Hamilton around that time and Edwin Starr came up from Cleveland. He’d just got back from service in Germany. We did a thing together called ‘Oh how happy’ but I hated it and gave him my writers’ share. It was a big mistake ‘cause it hit big with a white group (Shades of Blue) he gave it to but I just thought it was junk. Around the same time, he hit with ‘Agent double O soul’ and I became his tour manager.

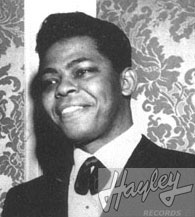

Luther Dixon

We were in New York with Edwin and that’s where I first met Luther Dixon. He’d had a lot of hits on people like the Shirelles and Chuck Jackson. He was working with Betty Lavette on sessions for Nate McCalla at Bell Sound and was looking for songs. Bob Hamilton and me came up with ‘I feel good (all over)’ and she cut that. Luther wanted more songs from me so that’s when we worked with an artist he had called Billy Hambric.

Luther used two of my songs on that session ‘I found a true love’ and ‘She said goodbye’ but they didn’t pan out like he wanted. Luther got to work with the Platters but he wasn’t sure which direction to take them in so I convinced him to come to Detroit and work with them there. We had a lot of great studios, some of the best session musicians and songwriters, arrangers and producers everywhere. I hooked him up with Popcorn and they hit it off straight away. Luther loved it in Detroit ‘cause it was like one big family. Everyone knew each other and it was good times. Golden World was the best place I worked at ‘cause of the camaraderie of the people there. I met some incredible people there too — people I stayed friends with. Guys like Mike Terry, Fred Bridges, all the Hamilton boys (Robert ‘Rob Reeco’, Albert ‘Al Kent’ and Eugene ‘Ronnie Savoy), Mr. Wingate and so many others.”

Mancha & Kent

Another operation that utilised Mancha’s skills was a label set up by the parents of Berry Gordy’s first wife, Thelma Coleman in 1962, ‘Thelma’s Records’ later changed to ‘Thelma’. “ Mr. And Mrs. Coleman (Robert and Hazel) had seen Berry Gordy, their ex son in law, become successful and thought that they could do it too. Don Davis, who I’d known from way back, brought me in. The Colemans depended on Don ‘cause he had the musical expertise and knew a lot of people. He was a musician on call and played on a lot of sessions — he played everywhere, even on Motown sessions. He also had aspirations to be Berry Gordy, even before Berry! I was doing so much freelancing around that time (1965/66) that I was all over the place.

Mancha and McMurray

Don introduced me to Clay McMurray who was just starting out and we hit it off straight away. We did sessions with Billy Kennedy, and I remember thinking that ‘Groovy generation’ was gonna be a stone smash. When I got with Clay, I already had the tracks ‘cause I’d already cut them. I would get an idea in my head, play the chords out to the arranger and then he would write them out for the musicians and then we’d record it. I’d take the finished master tape away with me ‘cause I’d paid for the session. I don’t think anyone else worked like that, but that’s the way I did it. I never knew who the track was for or what the lyrics would be until I came to work with a vocalist. If I came across an act I wanted to record I would just take them into a studio to dub the vocals over the track. Sometimes it would take two to three days for a singer to get a song. Most of them didn’t know their ass from a hole in the ground. Don Davis and Mr. Coleman put Clay and me with Billy Kennedy and Emanuel Laskey to start with and we worked on the lyrics together.

We did ‘Sweet lies’ on Emanuel and we used the same track on ‘I’m lonely’ on Martha Star, which was good for me ‘cause I got two royalty cheques. Emanuel was good to work with ‘cause he’d got such clear diction and he’d got a great voice. A lot of other cats would mumble but he was clear and real easy to work with. We’d always record him in the morning when his voice was soft. I wrote ‘Peace loving man’ for him. I liked Martha Star too. She did one of my songs, ‘Love is the only solution’. That was an ‘acid’ song. I was high as a kite on acid when we did that —that’s why there is all that crazy psychedelic noises in it. I swore I would never do that again, and I never did.” When Thelma Records finally wound up operations Mancha had already moved on. “I really liked Robert and Hazel Coleman. We became good friends, but I couldn’t stay in one place all the time. I was doing so much freelancing I was always on the move. I went to Chicago or New York — wherever they needed me. But they had a good operation. I think they just ran out of money in the end. Some great talent got their start with the Colemans. Norman Whitfield started there and so did Richard Street. Some of their first sessions were recorded at Motown too you know. Berry and Thelma got along, even after they split up, and I know Berry would let her use the studio.”

Mancha’s frequent travelling resulted in professional liaisons that eventually turned into business opportunities. One such meeting occurred in New York when he met Johnny Terry. “He was with the Drifters when I first met him. I was with Edwin’s tour. He told me he really wanted to produce and write for other acts. He was from Detroit so coming home for him wasn’t a problem. Around the same time I’d got with a business partner called Don Montgomery. He was a gangster — a lot of small labels were either set up or funded by gangsters, not only in Detroit, but in other cities too, because they had excess money. Don would refer to himself as a ‘goodwill ambassador’! We set up Empire Productions and that was a real good time. Don didn’t care what stuff cost. He just wanted the best, so we had the best musicians, arrangers, studios and whatever we needed. I always used the local musicians ( now collectively known as the ‘Funk Brothers’) ‘cause they picked stuff up so quickly and that could save you a lot of money in wasted studio time.

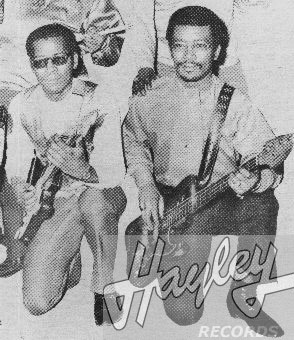

Just Brothers - Jimmy and Frank Bryant

One of the first things we did was on one of Johnny’s acts, the Just Brothers. They had a sound that was unique, kinda the opposite of Sam and Dave, a lighter harmonic sound. We did one of my songs, ‘Carlena’. It was actually about my girl at the time. We were real close and had a child together. Her name was ‘Carlean’ but we changed it so it had an extra syllable to fit with the chorus. I worked with one of Eugene Hamilton’s (Ronnie Savoy) acts then too. They were two guys from Cleveland called Taurus and Leo — that was their birth signs. I did ‘I ain’t playing baby’. Then we did the Honey Bees too. They were a group I saw singing in a club one night. I wrote ‘Let’s get back together’ for them with Edwin. That’s when Johnny and me started producing. I did some songs for LeBaron Taylor too on one of his acts, Chalfontes. He named them after a street in Detroit he liked the sound of but no one could say it properly so we had to explain how to say it on the record label. I did a couple of tunes for him but he only credited me with one of them (Confessin’ my love for you)”

Of all his achievements, the material Mancha wrote for the artist known as ‘Jack Montgomery’ arouses the most excitement. “I first saw him singing in a club in Windsor, Canada just over the Detroit River. I was over there to see the taping of a TV show, Robin Seymour’s ‘Swingin’ Time’ and his voice just knocked me out. He had a real natural talent and was very sophisticated. He was 19 when I met him and was training to be a draughtsman. When we started planning, we knew we had to change his name. It was Marvin Jones, but we thought that sounded too black if we were going to get airplay on white radio. So we settled on ‘Jack’ from Jack Kennedy, who we all liked, and we used Don’s last name to come up with ‘Jack Montgomery’.

We did the same thing with Clyde Wilson, who was a hell of a songwriter, but he wanted to record too. He was a great singer. Don Davis and LeBaron were trying to come up with names that sounded less black. One of the names they considered was ‘Corey Strickland’! That’s how desperate they were. In the end they asked me if I minded them using my last name and I said ‘Sure’ so they added ‘Steve’ and that’s how he got his name. The songs we did on Jack Montgomery were the best I ever wrote, and he co wrote most of the songs with me. We did ‘Dearly beloved’ first, with Dennis Coffee and Mike Theodore arranging. It was the first arrangement they had ever done and man did they nail it. We recorded that session at United with the top sessions guys and the Detroit Symphony. That was the first time he had ever recorded and he picked it up quickly. The other songs we did, ‘Do you believe it’ and ‘Never leave me’ were just as good but we only used ‘Do you believe it’ on the B-side of ‘Dearly beloved’. Johnny had contacts in New York. He knew Florence Greenberg who ran Scepter/Wand and he did a deal with her to distribute it too.

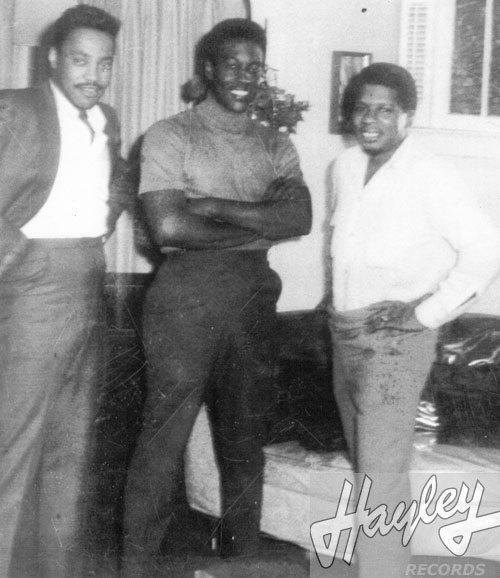

Jack Montgomery(Marvin Jones), Jay Davis and Johnny Terry

We did another session with him too on a song I wrote with Fred Bridges, ‘Don’t turn your back on me’. Man, I really loved that song especially the way he sang it. I can remember teaching him the song with his brother in law, Jay Davis (of the Tempos) and he really got into it when we recorded it.” Sadly, things turned awry between Mancha and Terry that eventually ended Jack Montgomery’s short career. “ I guess I was too laid back for him and he didn’t like my style. Johnny was talking in his ear, promising him the big time and all that stuff and that’s when they split from me. It was a real error of judgement for Jack going off with Johnny especially when Johnny ran off with the tapes we had left in the can. Johnny spoke to Uni and got a deal for a release on one of their labels (Revue) on a song I had written with Jack called ‘Baby baby take a chance on me’. They only had the vocal and the track but that was enough I guess. Don Montgomery was real mad and wanted to give them both a ‘spanking’ but I knew it wouldn’t sell ‘cause I could put a block on it, and I convinced him to back off. I made a few calls to DJs and distributors I knew and told them what had happened and they wouldn’t touch it. I sure saved Johnny from a whooping. It was real sad, the way that went down ‘cause he was a hell of a talent and would have broken big in time. He had too much talent.” Marvin Jones died in 1982 of complications associated with diabetes.

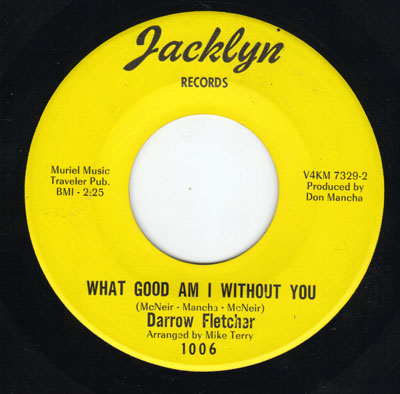

By 1967 Mancha found himself shuttling between Detroit and Chicago. “ I had two homes back then — one in Detroit and one in Chicago. I started writing with Harry and Mary McNeil who were really talented songwriters. We did some songs for the Soul Twins in Detroit and Darrow Fletcher over in Chicago. They were good sessions —I had Donny Hathaway on piano and I used Phil Upchurch too. Around that time my good buddy Mike Terry had been signed by Epic to write and record some of their acts and he asked me if I’d got anything he could use. Fred Bridges and me had written a thing called ‘Gone but not forgotten’ that Mike used on one of his artists (Johnny Robinson) I’d known Mike since the really early days. He was around in Popcorn’s first band and was pulled in to Motown at the very start playing his baritone. He had a unique sound that other sax players just couldn’t get. He was one of the true ‘Funk Brothers’ — he would sit with them and play his frills while they were laying down the rhythm track, then he would play on the horn parts later too. His horn became part of the rhythm section ‘cause Berry wanted a baritone to be right in the mix — they all knew that. We were like brothers. He was a genius, really quietly spoken but real funky too. A funky quiet guy! He left Motown in 1967 and they couldn’t replace him. If you look at the songs they were doing after he left, there is no more baritone sax on them. I guess he got frustrated ‘cause they wouldn’t let him do anything else but play his horn. He wanted to write, arrange and produce too but there was no opportunity with all the people they had there so he did his own thing. Whenever I used him to arrange he was always on the money and he had such a distinctive baritone sound we all used him on our sessions. Him and Jack Ashford set up a production company (Pied Piper) when they left Motown but Jack screwed Mike over when he got with Shelley Haims and they got a deal with a major (RCA). That’s when he got with Epic in Chicago, around ’68 I believe. He also arranged an album for Ollie (McLaughlin) on Barbara Lewis in Chicago and I gave Ollie a song that that project called ‘The stars’ that they liked. ”

As the 1960s progressed into the early 1970s the scope and range of Mancha’s influence grew. In 1969 he headed south to work in Memphis with the Dynamics at Tommy Cogbill’s American Sound Studio. “I got to know a lot of guys from Memphis over the years, especially being out on the road with Edwin, including Darryl Carter, who became a close friend. We wrote a couple of things together. That’s what it was like back then. If you met someone who wrote songs like Darryl, and man, he wrote a ton of songs for lots of artists, you sat and wrote with them. Don Davis had some connections down there too, with Al Bell at Stax. Mack Rice was down there, and of course there was Pickett. It was a lot more laid back in the South, especially when they recorded. We’d be trying to get the tracks finished as soon as we could in Chicago or Detroit or New York, but down there they just worked on it ‘till they got what they wanted. The Dynamics were managed by Ted White, who was married to Aretha and he had contacts with Atlantic through her. I think it was Jerry Wexler’s idea to record them in Memphis. They used two of my songs on their album, ‘Too proud to change’ and ‘Love that I need’. I was doing a lot of freelancing back then. That’s when I started going to LA a lot more. I’d known Ike Turner from the old days and when he asked me to help him with ‘Nutbush City Limits’ I did. That was a smash. I wrote some real good songs on Tina Turner but they didn’t use ‘em. I got to work with Ike Turner’s band, ‘Family Vibes’ later too. We hit with ‘Beauty is in the eye of the beholder’.

Loretta Kendrick

Mickey Stevenson had moved down there from Motown. He set up Venture Records with Clarence Paul and I’d hang with those guys too. I actually helped them get a lead singer for a group they put together called the Naturelles ‘cause I’d done a song on a girl out of Detroit called Loretta Kendrick, which I didn’t put out, but they heard her and liked what she did, so they put her with the group. In fact Clarence Paul actually sings a line in her song. I wrote that song with Dick Cooper who was also a prolific songwriter.” The record, ‘My feelings keep getting in the way’ was eventually released on Hayley Records in UK in 1999 to critical acclaim. Another unreleased Mancha composition, that saw the light of day around the same time, was a tribute to Marvin Gaye that he wrote following his untimely passing in 1984 — ‘Thank you for the songs Marvin’.“ I’d known Marvin since the early days back in Detroit and really felt it when he passed. I wrote it not long after he died and recorded it on Darryl Carter’s nephew Tim Carter, but I figured it was too soon after his death to put it out, and felt it might look like we were cashing in so I kept it in the can and kinda forgot about it.”

The secret, if there is one, to Don Juan Mancha’s incredible ability to weave emotions, feelings and sentiments into his songs is probably best summed up by the man himself. “All my songs were heartfelt. I couldn’t have done them if I hadn’t been in situations or experienced them for myself. I met a lot of different people and went through a lot of different times — good and bad, and that’s what I drew from. I was close with my brother Pedro and we wrote some things together, but it was the same thing. We couldn’t make it up. It had to have happened.” From a purely business point of view, expediency and efficiency seemed to prevail. “As a freelancer, I was always thinking that if a song came to me I had to get it down on paper and on tape, so that I wouldn’t forget it, and then try to get it with someone as soon as I could. I was always recording tracks so that if someone wanted a song I only had to add the lyrics. I always had a slew of quarter inch tapes with tracks on with me, wherever I went so that I was ready.” Although Mancha wrote with scores of talented writers he wouldn’t work with just anyone. “I passed on working with a lot of people. I wouldn’t work with people I didn’t like or thought I couldn’t work with. I didn’t prostitute myself just to make a buck.”

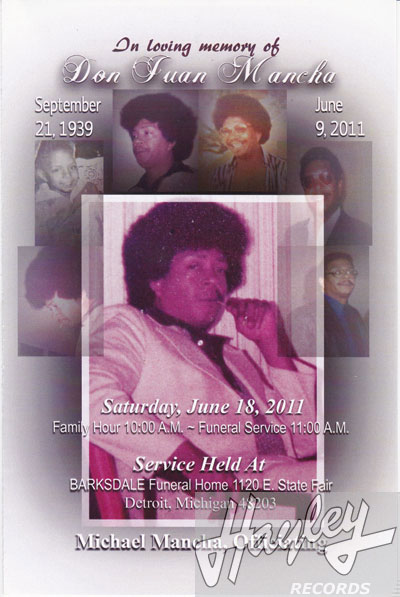

Don Juan Mancha passed away in Detroit on 9th June 2011.

Rob Moss

Feb 2013

http://www.hayleyrecords.co.uk

Related Soul Source Articles

-

2

2

-

4

4

Recommended Comments

Get involved with Soul Source

Add your comments now

Join Soul Source

A free & easy soul music affair!

Join Soul Source now!Log in to Soul Source

Jump right back in!

Log in now!