IVY JO HUNTER

Motown’s phenomenal success in the 1960s was due, in large part, to the abundance of talented songwriters the company nourished and nurtured from within. From his own experience in the 1950s with Jackie Wilson, Berry Gordy Jnr. knew that good songs were the lifeblood of commercial musical success for a record company. It didn’t matter how talented the performers, musicians or producers might be — without great songs, it would all be for nought. In the early days, the bulk of compositions came from himself, Barrett Strong, Smokey Robinson, Robert Bateman and Janie Bradford, but as the carnival expanded, additional local talents were welcomed aboard and a surge of melodious ingenuity erupted. Eddie Holland and Lamont Dozier had begun their careers as vocalists at Motown, but decided to join forces with Eddie’s brother Brian to concentrate on song writing and production at the company, whilst a new recruit, fresh out of Army service, entered the fray with little fanfare and hardly any influence.

George Ivy Hunter was enlisted by Motown A & R director William ‘Mickey’ Stevenson in 1963 on a referral from in house tenor sax player Henry ‘Hank’ Cosby, who had worked with him at another local studio and sensed his potential. Stevenson’s power and prestige within the Motown hierarchy allowed him to dictate, and receive, a 50% share of all Hunter’s songs during their initial ‘negotiations’, even though, in the bulk of cases, he would contribute very little or nothing at all. Interestingly, Hunter signed four separate contracts at his induction — songwriter, artist, producer and artist manager, and amended his name slightly to become known as ‘Ivy Jo Hunter’. Over the next eight years, he would contribute some of Motown’s most beautiful and important songs and become one of the most successful song writers in the world, composing material for the Temptations, Marvin Gaye, Gladys Knight & the Pips, Four Tops, Isley Brothers, Spinners, Supremes, Marvelettes and many more. His songs have been ‘covered’ by such diverse talents as Mick Jagger, David Bowie, Augustus Pablo, Bryan Ferry, Eric Clapton, Bonnie Rait, Phil Collins, Aretha Franklin and scores of others.

Ivy Hunter graduated from the prestigious Cass Tech. in Detroit around the same time as arranger extraordinaire Paul Riser, famed producer/arranger Dale Warren and baritone sax man Andrew ‘Mike’ Terry, who all ended up working for Motown. After a brief stint in the US Army, as an electrical engineer, he tendered songs to the fledgling Correctone set up on Grand River Avenue and, in late 1962, was contracted as a songwriter and session musician for the label. His memories of those times are lucid and incisive. ‘My mother didn’t want me to go into the music business. She thought it was no good, so I studied commercial art at Cass but still played trumpet and baritone sax in the Detroit All City Orchestra. When I came out of the army the music scene in Detroit was buzzing.

I got into Correctone as a player then started to write. I met people like Joe Hunter and Hank Cosby, who were great players but could arrange too. I hung with Don Juan Mancha who helped me with my song writing. When the owner, Wilbur Golden, sold everything to Ed Wingate the only contract Wilbur would not sell to him was mine! He gave me a release and I went to Motown.’ Despite Hank Cosby’s recommendation, he still had to wait for Mickey Stevenson. ‘I would go to the lobby of the building on Grand Boulevard and wait to see him. It seemed like a couple of weeks before he finally saw me but he liked what he’d heard and seen, so I signed.’ Hunter bears no ill will against the song writing deal Stevenson forced on him. ‘Without Mickey I would never have got into Motown at all. When I was there he would be in my corner and there were songs that he gave me credit on that I didn’t contribute anything to. Songs like ‘A thrill a moment’, ‘ I’m still loving you’, ‘My baby loves me’ on Martha Reeves and most of the other songs he did on Kim Weston. When Mickey left in ’66 they gave me the choice to remove his name from my songs but I left it on. He did a lot for me. I always felt indebted to him.’

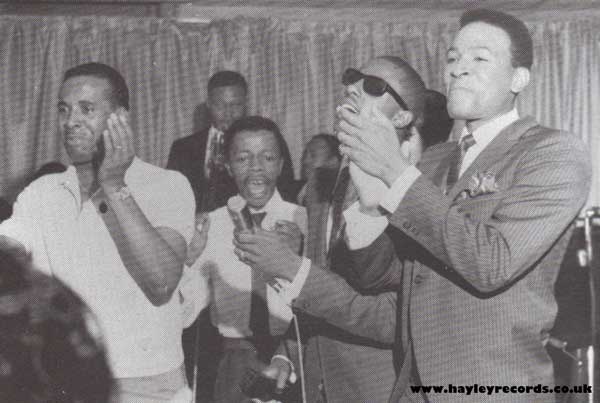

Mickey S and Ivy on Teen Tv Motown Special

Ivy Hunter’s time at Motown did not begin very auspiciously. ‘I always felt like an outsider, probably because I hadn’t been there since the inception, and I didn’t get involved in all the petty politics that was going on. When I came in my style was so different from the accepted Motown sound — Smokey was Smokey, HDH did the same thing over and over, but my songs were different every time. I brought a lot of different instruments in too, which gave them different sounds. At the start, they tended to give me artists that hadn’t had a hit or who needed maybe an album track. That’s how I got with the Tops — they were ‘new’ artists. I had four songs on their first album and then as soon as they hit HDH did everything on them and I never really worked with them for a long time. That’s the way it was. There was a hierarchy within the building. Smokey only ‘lost’ the Tempts when Norman Whitfield came in ‘cause he (Whitfield) got into the upper circle and got hits right off the bat. Whoever had the most influence with Berry Gordy and his lieutenants got to work with the most successful artists.’ Hunter’s style was certainly multifarious and the four songs he cites on the Four Tops first album go a long way to explain his genius. The magnificent ‘Ask the lonely’ became a classic song almost immediately, garnering cover versions aplenty, and becoming, along with ‘What becomes of the broken hearted’, the anthem of heartbreak; sorrow, lost love and anguish. ‘Teahouse in Chinatown’ with it’s lilting oriental motif, ‘Don’t turn away’ and ‘Sad souvenirs’ are, indeed, as dissimilar to each other, whilst maintaining their uniqueness and originality. Hunter’s memory of ‘Ask the lonely’ casts new light on its provenance. ‘I originally conceived it as a fast dance tune ‘cause that was what they liked us to do at the time. I guess they were aiming at the teenage market. Mickey was lining Kim Weston up to sing it but then I suddenly saw it as a ballad. It was like I’d had an epiphany or something. I recorded it myself to make it easier for the artist singing it to learn it. I did that a lot.’

Levi, Ivy, Stevie and Marvin singing at his 23rd birthday party

Conversely, a song that was originally written as a ballad, morphed into a fast song that would become Hunter’s most successful song ever...

In its earliest form ‘Dancing in the street’ had different lyrics and was conceived as a melancholy song. ‘I’d got the melody in my head but I hated it. We were in Mickey’s apartment with Marvin when I first tried it out on them. Marvin said that it should be faster and would cause ‘dancing in the street’, so that gave us the title. Mickey added all those place names and the following day we recorded it on Martha and the Vandellas. Mickey did actually offer it to Kim Weston (his wife), but she turned it down. She said it was too childish.’

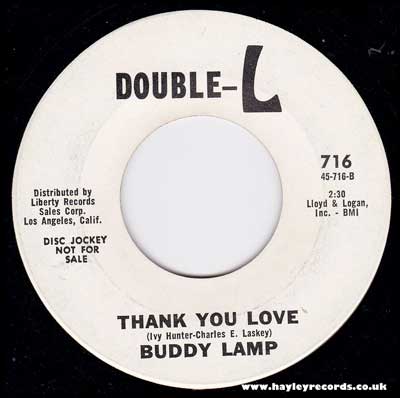

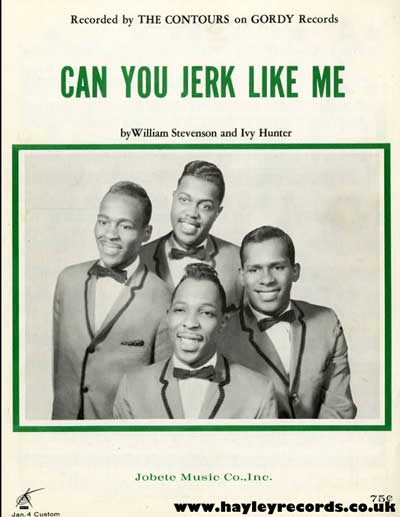

Hunter’s ability to create commercially appealing songs never waned. ‘The first song I did when I came in was ‘Sweet thing’ for the Spinners and that made some noise. My first big hit was ‘Can you jerk like me’ for the Contours but I provided songs for quite a range of other artists too. I would write on my own but once I became more successful they would put other people with me so that I could show them the ropes. Once they’d developed, they would leave me and work on their own. I would produce my own stuff too, so I could make it sound how I wanted. The only place I had no control was on the board in the control room. They never let me in there and never taught me how the mastering and mixing was done. I remember writing a song with Stevie (Wonder) called ‘Loving you is sweeter than ever’ on the Tops but I always thought that they messed up the mastering on that song and didn’t make it sound like I wanted. They always interpreted my songs without my input.’

Some relatively unfamiliar names appear along side Hunter’s on some of his creations, particularly Bertrice Verdi. ‘She was an aspiring songwriter who didn’t really contribute anything of note at all. She was really cute though! Seriously, I would work with pianists who would provide good, melodic tunes that I could put my lyrics on. Vernon Bullock, Jack Goga and Steve Bowden all worked with me like that. We were always collaborating with each other back then. I wrote with Sylvia Moy, Stevie, Smokey, Clarence Paul, Eddie Holland, Shorty Long on occasion. I remember one tune I wrote with Stevie, ‘My love is your love (forever)’ That one had a Beatles influence. I’d just heard the Sergeant Pepper’ album and thought I’d try and write a song in the same style. It was good but I don’t think we succeeded!’

Ivy Jo Hunter and Chuck Jackson

Although Hunter worked with some of the first string artists like the Temptations (‘Born to love you’, ‘Sorry is a sorry word’ ‘Just another lonely night’) or Marvin Gaye (‘Lucky lucky me’, ‘You’, ‘Sweet thing’, ‘It’s a desperate situation’), this was rare, due once again to the stranglehold certain writers and producers would had on these artists. ‘ I never got to work with the Supremes until Diana Ross had left. And when I did get with the Tempts or Marvin it was only on a few songs, and even then they might not actually get released …or promoted. As time went on the company concentrated on only a few of the most successful artists and left many people out of the loop. If they did put things out there wasn’t the same promotion and push as the bigger artists got. These were the artists assigned to me. People like the Marvelettes, the Isley Brothers, Chuck Jackson, the Spinners and several others.’ A list of just a small selection of the songs he wrote for these artists only proves what a truly remarkable writer he is.

Isley Brothers - ‘Behind a painted smile’, ‘Why when love is gone’ ‘Seek and you shall find’, ‘One too many heartaches’ ‘Got to get you back’ ‘My love is your love (forever)’

Spinners — ‘I’ll always love you’ ‘Truly yours’ ‘Too late I learned’ ‘Sweet thing’

Marvelettes ‘Danger heartbreak dead ahead’ ‘ I’ll keep holding on’

Brenda Holloway ‘Keep steppin’ (and never look back)’ ‘Lonely boy’

Andantes ‘That’s a funny way’

Gladys Knight & the Pips ‘The stranger’

Chuck Jackson ‘To see the sun again’ ‘What am I going to do without your love’

Four tops ‘Yesterdays dreams’ ‘Just a little love (before my life is gone)‘ ‘Fantasy’

Edwin Starr ‘I can’t escape your memory’

Monitors ‘Share a little love with me (somebody)’

Another of his frustrations related to his contract as a singer. ‘Even though I’d signed a contract as an artist, back in ’63, they hadn’t put anything out on me in seven years. So I asked for my song writers contract back and that seemed to work. They put a couple of tunes out on me but they didn’t promote them. In Detroit, my tune ‘I remember when (dedicated to Beverley)’ hit the number one spot on at least two of the radio stations but they didn’t stock the local stores with the record, so it just fizzled out.’

Outside Hitsville at Tommy Good 'demonstration' (Ivy is next to Berry Gordy)

The sheer range of Hunter’s lyrics, and the depth of emotion he drew from, often confounded artists he worked with. ‘Not everyone could understand or interpret my songs the way I wanted. Some would take a long time to understand the concept and how I wanted it be delivered. Others could pick it up quickly — Bobby Taylor was great that way. I’d show him a song and he’d be right on it. He’d add his own vocal gymnastics. Marvin was good too. He’d take your song and make it better. He really was great to work with. He was humble and had no show at all.’ Mutual respect was a currency in high demand on Ivy Hunter’s sessions. ‘Yes I always treated anyone I worked with the utmost respect and tried to be as patient as I could. Most of the time it worked. I do remember one time. I was working with the Tempts on ‘Sorry is a sorry word’ when David Ruffin complained that the song was too high for his vocal range. I quietly told him to take a break and called Paul Williams over in his earshot. I never saw a guy move back to his place and want to get started again so quick! It was a privilege to work with the talent they had at Motown.’

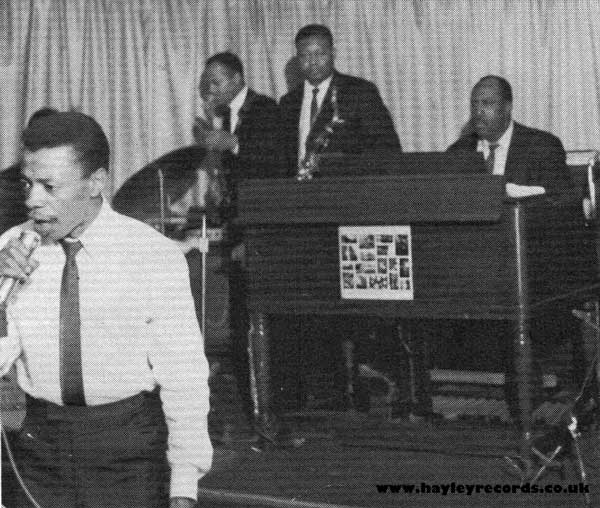

Ivy and the Funk bros at the same birthday party

The importance of the musicians at Motown is not lost on Ivy Hunter. ‘Getting a good (backing) track was crucial ‘cause that set up the whole feel for the song. We were really fortunate to have such a tight band. A group of guys who could set up a groove and hold it together. They were a very tight unit. I always started with drums and bass. Nobody could play drums like Benny Benjamin and no one had to teach him anything ‘cause he would be right there. Jamerson was real quick too. Paul Riser would transcribe the bass line for Jamerson from what I’d play on the piano and then he’d come up with something. Then Benny would slide right in. We would usually use three guitars — Robert White would play that ‘chink, chink’ stuff, Eddie Willis played rhythm and Joe Messina would put fills in, even if you hadn’t given him a part to play. He would always come up with something to make your song better. Once we’d got the rhythm part done we’d start adding other instruments where I thought they should be. It’s funny but on some sessions you just started things off and the band ran it themselves. If they felt it and got into the groove, you knew it was gonna be great. A tune we did ‘Share a little love with me (somebody)’ was like that. That was what I felt was my job as a producer. I don’t play the instruments but I do play the players!’

Ivy Hunter’s last days at Motown still smoulder with acrimony and regret. ‘Once Mickey was fired I was on my own. He had always helped me with my affairs when it came to royalties and related business matters like that, but without him there I felt like I was against everyone, and I had no business experience at all. Then, like a thunderbolt, they suddenly upped and moved to LA. I went to California not long after they’d moved and tried to find out whether they wanted me to move down or stay where I was. The answer I got was ‘Go back to Detroit and ask them.’ The only people still in Detroit representing the company were an administrator and the head accountant! I guess I got my answer. They reneged on an advance I was supposed to get on a new contract and simply just walked away from me. I was of no value to them. I really had to fight to get royalties too and I’m sure I didn’t get my proper monies due. It ended badly for me.’

The flames of creativity were re kindled not long afterward however, when he set up Probe Productions and began working with local Detroit talent. A string of 45 releases and ‘outside’ productions for groups like Funkadelic and the Dells during the 1970s, culminated in a hit song that reverberates to this day. ‘ I wrote ‘Hold on (to your dream)’ with Vernon Bullock around 1978 and we recorded it on Wee Gee. He was a guy I knew from his time with the Dramatics. He did a great job on the song and it shot to the top. Do you know that it has been used at more Graduation ceremonies than any other song! It was even re worked by a guy called Trick Daddy in 2012 and hit again. God sure gave me one with that song.’

Ivy Hunter continues to write and produce great music. The hope for Motown fans is that his unreleased material and the planned album, that was shelved at the time, will finally see the light of day.

Rob Moss

Oct 2013

Related Source Magazine Articles

Author Profile: Rob Moss

Rob Moss

Rob Moss is a contributor at Soul Source, covering Northern Soul, Rare Soul, and modern soul scene stories.

Rob Moss has been a Soul Source member since .

No custom author profile added yet

Explore more of their work on their author profile page.

Recommended Comments

Get involved with Soul Source